Hola amigos: A VUELO DE UN QUINDE EL BLOG., nuestro Universo, es una enigma que nunca acabaremos por descubrir misterios de su composición, que desubica a los científicos, que siguen sus investigaciones con sus observatorios y telescopios, justamente el descubrimiento de la Supernova SN2016iet, por el telescopio GAIA de la Agencia Espacial Europea ESA, han comprobado que: "

El Observatorio Gemini consta de dos telescopios gemelos ópticos/infrarrojos de 8,1 metros ubicados en ambos hemisferios de la Tierra que se encuentran operativos científicamente desde el 1983.

Está conformado por una cooperación internacional por los países de EE. UU., Canadá, Gran Bretaña, Brasil, Francia, Argentina, Australia, y Chile como país huésped. Es administrado por la Asociación de Universidades para la Investigación en la Astronomía (AURA) bajo un acuerdo de cooperación con la Fundación Nacional de Ciencias de Estados Unidos (NSF).

Total Annihilation for Supermassive Stars

August 15, 2019

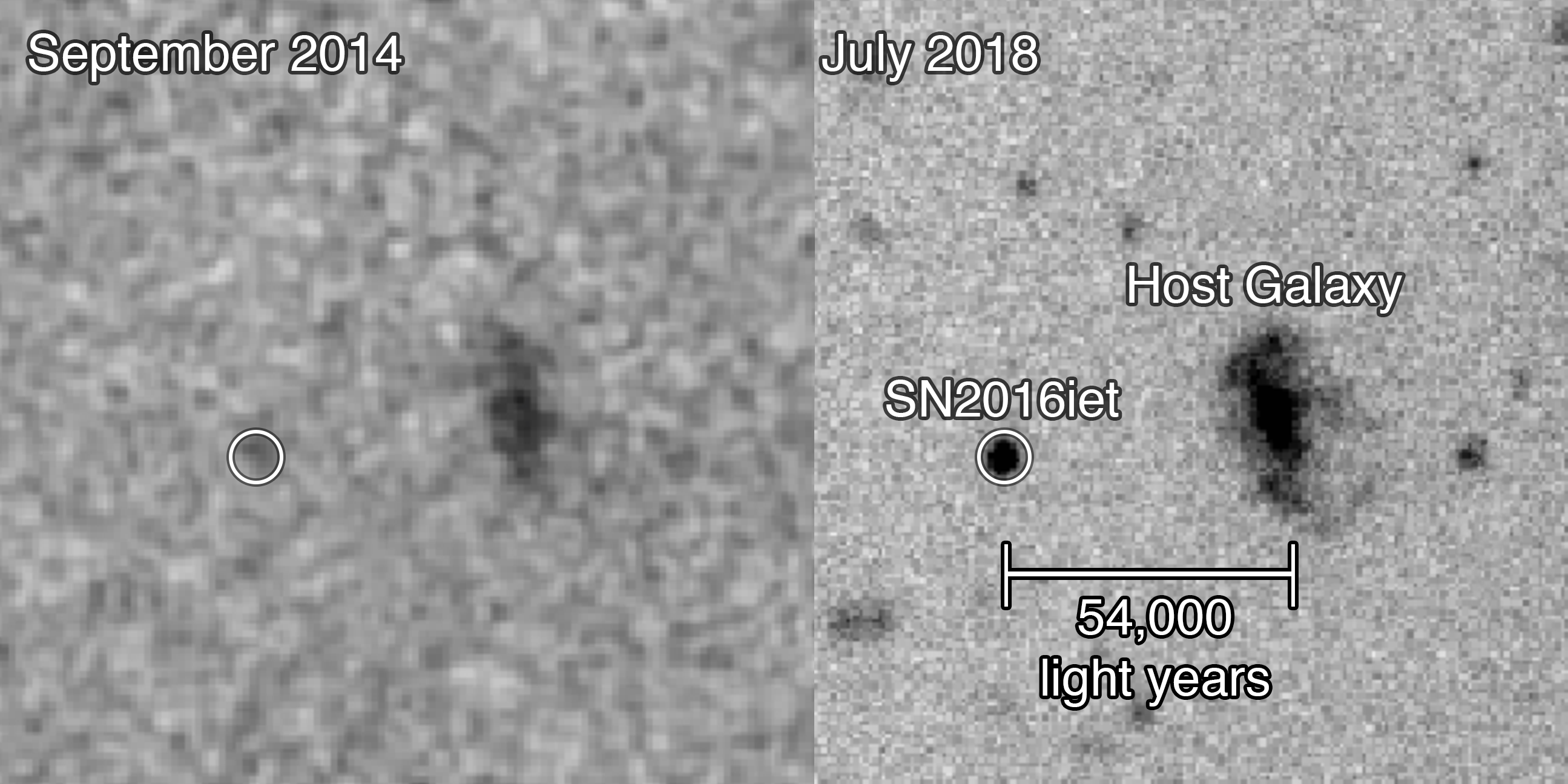

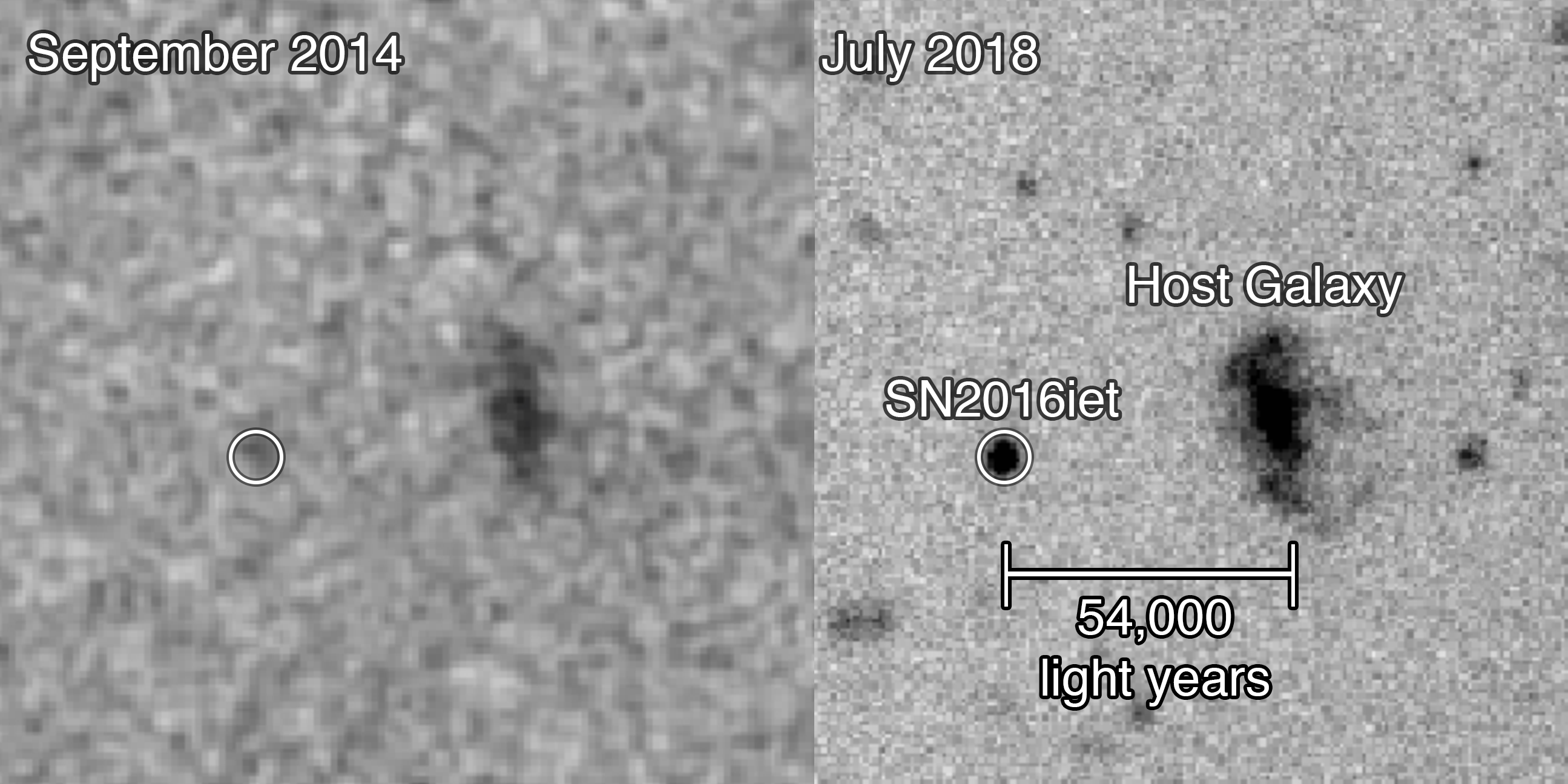

Figure 2. Image of SN 2016iet and its most likely host galaxy taken

with the Low Dispersion Survey Spectrograph on the Magellan Clay 6.5-m

telescope at Las Campanas Observatory in i-band on July 9, 2018.

Figure 2. Image of SN 2016iet and its most likely host galaxy taken

with the Low Dispersion Survey Spectrograph on the Magellan Clay 6.5-m

telescope at Las Campanas Observatory in i-band on July 9, 2018.

The European Space Agency’s (ESA) Gaia satellite first noticed the supernova, known as SN 2016iet, on November 14, 2016. Three years of intensive follow-up observations with a variety of telescopes, including the Gemini North telescope and its Multi-Object Spectrograph on Maunakea in Hawaiʻi, the CfA | Harvard & Smithsonian's MMT Observatory located at the Fred Lawrence Whipple Observatory in Amado, AZ, and the Magellan Telescopes at the Las Campanas Observatory in Chile, provided crucial perspectives on the object’s distance and composition.

“The Gemini data provided a deeper look at the supernova than any of our other observations,” said Edo Berger of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and a member of the investigation’s team. “This allowed us to study SN 2016iet more than 800 days after its discovery, when it had dimmed to one-hundredth of its peak brightness.”

Chris Davis, program director at the National Science Foundation (NSF), one of Gemini’s sponsoring agencies, added, “These remarkable Gemini observations demonstrate the importance of studying the ever-changing Universe. Searching the skies for sudden explosive events, quickly observing them and, just as importantly, being able to monitor them over days, weeks, months, and sometimes even years is critical to getting the whole picture. In just a few years, NSF’s Large Synoptic Survey Telescope will uncover thousands of these events, and Gemini is well positioned to do the crucial follow-up work.”

In this case, this deep look revealed only weak hydrogen emission at the location of the supernova, evidence that the progenitor star of SN 2016iet lived in an isolated region with very little star formation. This is an unusual environment for such a massive star. “Despite looking for decades at thousands of supernovae,” Berger resumed, “this one looks different than anything we have ever seen before. We sometimes see supernovae that are unusual in one respect, but otherwise are normal; this one is unique in every possible way.”

SN 2016iet has a multitude of oddities, including its incredibly long duration, large energy, unusual chemical fingerprints, and environment poor in heavier elements — for which no obvious analogues exist in the astronomical literature.

“When we first realized how thoroughly unusual SN 2016iet is, my reaction was ‘Whoa – did something go horribly wrong with our data?’” said Sebastian Gomez, also of the Center for Astrophysics and lead author of the investigation. The research is published in the August 15th issue of The Astrophysical Journal.

The unusual nature of SN 2016iet, as revealed by Gemini and other data, suggest that it began its life as a star with about 200 times the mass of our Sun — making it one of the most massive and powerful single star explosions ever observed. Growing evidence suggests the first stars born in the Universe may have been just as massive. Astronomers predicted that if such behemoths retain their mass throughout their brief life (a few million years), they will die as pair-instability supernovae, which gets its name from matter-antimatter pairs formed in the explosion.

Most massive stars end their lives in an explosive event that spews matter rich in heavy metals into space, while their core collapses into a neutron star or black hole. But pair-instability supernovae are a different breed. The collapsing core produces copious gamma-ray radiation, leading to a runaway production of particle and antiparticle pairs that eventually trigger a catastrophic thermonuclear explosion that annihilates the entire star, including the core.

Models of pair-instability supernovae predict they will occur in environments poor in metals (astronomer’s term for elements heavier than hydrogen and helium), such as dwarf galaxies and the early Universe — and the team’s investigation found just that. The event occurred at a distance of one billion light years in a previously uncatalogued dwarf galaxy poor in metals. “This is the first supernova in which the mass and metal content of the exploding star are in the range predicted by theoretical models,” Gomez said.

Another surprising feature is SN 2016iet’s stark location. Most massive stars are born in dense clusters of stars, but SN 2016iet formed in isolation some 54,000 light years away from the center of its dwarf host galaxy.

“How such a massive star can form in complete isolation is still a mystery,” said Gomez. “In our local cosmic neighborhood, we only know of a few stars that approach the mass of the star that exploded in SN 2016iet, but all of those live in massive clusters with thousands of other stars.” To explain the event’s long duration and slow brightness evolution, the team advances the idea that the progenitor star ejected matter into its surrounding environment at a rate of about three times the mass of the Sun per year for a decade before the star blew itself into oblivion. When the star ultimately exploded, the supernova debris collided with this material powering SN 2016iet’s emission.

“Most supernovae fade away and become invisible against the glare of their host galaxies within a few months. But because SN 2016iet is so bright and so isolated we can study its evolution for years to come,” said Gomez. “The idea of pair-instability supernovae has been around for decades,” said Berger. “But finally having the first observational example that puts a dying star in the right regime of mass, with the right behavior, and in a metal-poor dwarf galaxy is an incredible step forward.”

Not long ago, it was not known if such supermassive stars could actually exist. The discovery and follow-up observations of SN 2016iet have provided clear evidence for their existence and potential for affecting the development of the early Universe. “Gemini’s role in this amazing discovery is significant,” said Gomez, “as it helps us to better understand how the early Universe developed after its ‘dark ages’ — when no star formation occurred — to form the splendor of the Universe we see today.”

Figure 2. Image of SN 2016iet and its most likely host galaxy taken

with the Low Dispersion Survey Spectrograph on the Magellan Clay 6.5-m

telescope at Las Campanas Observatory in i-band on July 9, 2018.

Figure 2. Image of SN 2016iet and its most likely host galaxy taken

with the Low Dispersion Survey Spectrograph on the Magellan Clay 6.5-m

telescope at Las Campanas Observatory in i-band on July 9, 2018.Harvard University press release available here.

A renegade star exploding in a distant galaxy has forced astronomers to set aside decades of research and focus on a new breed of supernova that can utterly annihilate its parent star — leaving no remnant behind. The signature event, something astronomers had never witnessed before, may represent the way in which the most massive stars in the Universe, including the first stars, die.The European Space Agency’s (ESA) Gaia satellite first noticed the supernova, known as SN 2016iet, on November 14, 2016. Three years of intensive follow-up observations with a variety of telescopes, including the Gemini North telescope and its Multi-Object Spectrograph on Maunakea in Hawaiʻi, the CfA | Harvard & Smithsonian's MMT Observatory located at the Fred Lawrence Whipple Observatory in Amado, AZ, and the Magellan Telescopes at the Las Campanas Observatory in Chile, provided crucial perspectives on the object’s distance and composition.

“The Gemini data provided a deeper look at the supernova than any of our other observations,” said Edo Berger of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and a member of the investigation’s team. “This allowed us to study SN 2016iet more than 800 days after its discovery, when it had dimmed to one-hundredth of its peak brightness.”

Chris Davis, program director at the National Science Foundation (NSF), one of Gemini’s sponsoring agencies, added, “These remarkable Gemini observations demonstrate the importance of studying the ever-changing Universe. Searching the skies for sudden explosive events, quickly observing them and, just as importantly, being able to monitor them over days, weeks, months, and sometimes even years is critical to getting the whole picture. In just a few years, NSF’s Large Synoptic Survey Telescope will uncover thousands of these events, and Gemini is well positioned to do the crucial follow-up work.”

In this case, this deep look revealed only weak hydrogen emission at the location of the supernova, evidence that the progenitor star of SN 2016iet lived in an isolated region with very little star formation. This is an unusual environment for such a massive star. “Despite looking for decades at thousands of supernovae,” Berger resumed, “this one looks different than anything we have ever seen before. We sometimes see supernovae that are unusual in one respect, but otherwise are normal; this one is unique in every possible way.”

SN 2016iet has a multitude of oddities, including its incredibly long duration, large energy, unusual chemical fingerprints, and environment poor in heavier elements — for which no obvious analogues exist in the astronomical literature.

“When we first realized how thoroughly unusual SN 2016iet is, my reaction was ‘Whoa – did something go horribly wrong with our data?’” said Sebastian Gomez, also of the Center for Astrophysics and lead author of the investigation. The research is published in the August 15th issue of The Astrophysical Journal.

The unusual nature of SN 2016iet, as revealed by Gemini and other data, suggest that it began its life as a star with about 200 times the mass of our Sun — making it one of the most massive and powerful single star explosions ever observed. Growing evidence suggests the first stars born in the Universe may have been just as massive. Astronomers predicted that if such behemoths retain their mass throughout their brief life (a few million years), they will die as pair-instability supernovae, which gets its name from matter-antimatter pairs formed in the explosion.

Most massive stars end their lives in an explosive event that spews matter rich in heavy metals into space, while their core collapses into a neutron star or black hole. But pair-instability supernovae are a different breed. The collapsing core produces copious gamma-ray radiation, leading to a runaway production of particle and antiparticle pairs that eventually trigger a catastrophic thermonuclear explosion that annihilates the entire star, including the core.

Models of pair-instability supernovae predict they will occur in environments poor in metals (astronomer’s term for elements heavier than hydrogen and helium), such as dwarf galaxies and the early Universe — and the team’s investigation found just that. The event occurred at a distance of one billion light years in a previously uncatalogued dwarf galaxy poor in metals. “This is the first supernova in which the mass and metal content of the exploding star are in the range predicted by theoretical models,” Gomez said.

Another surprising feature is SN 2016iet’s stark location. Most massive stars are born in dense clusters of stars, but SN 2016iet formed in isolation some 54,000 light years away from the center of its dwarf host galaxy.

“How such a massive star can form in complete isolation is still a mystery,” said Gomez. “In our local cosmic neighborhood, we only know of a few stars that approach the mass of the star that exploded in SN 2016iet, but all of those live in massive clusters with thousands of other stars.” To explain the event’s long duration and slow brightness evolution, the team advances the idea that the progenitor star ejected matter into its surrounding environment at a rate of about three times the mass of the Sun per year for a decade before the star blew itself into oblivion. When the star ultimately exploded, the supernova debris collided with this material powering SN 2016iet’s emission.

“Most supernovae fade away and become invisible against the glare of their host galaxies within a few months. But because SN 2016iet is so bright and so isolated we can study its evolution for years to come,” said Gomez. “The idea of pair-instability supernovae has been around for decades,” said Berger. “But finally having the first observational example that puts a dying star in the right regime of mass, with the right behavior, and in a metal-poor dwarf galaxy is an incredible step forward.”

Not long ago, it was not known if such supermassive stars could actually exist. The discovery and follow-up observations of SN 2016iet have provided clear evidence for their existence and potential for affecting the development of the early Universe. “Gemini’s role in this amazing discovery is significant,” said Gomez, “as it helps us to better understand how the early Universe developed after its ‘dark ages’ — when no star formation occurred — to form the splendor of the Universe we see today.”

Science Contacts:

- Edo Berger

Harvard University

Email: eberger"at"cfa.harvard.edu

Cell: (617) 335-7963 - Sebastian Gomez

Harvard University

Email: sebastian.gomez"at"cfa.harvard.edu

Phone: (617) 495-4142

Media Contacts:

- Peter Michaud

Public Information and Outreach Manager

Gemini Observatory, Hilo, HI

Email: pmichaud"at"gemini.edu

Desk: (808) 974-2510

Cell: (808) 936-6643 - Alyssa Grace

Public Information and Outreach Assistant

Gemini Observatory, Hilo, HI

Email: agrace"at"gemini.edu

Desk: (808) 974-2531 - Amy Oliver

Public Affairs Officer

Fred Lawrence Whipple Observatory

Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian

Email: amy.oliver"at"cfa.harvard.edu

Desk: (520) 879-4406

Gemini Observatory

https://www.nationalgeographic.com.es/ciencia/aniquilacion-total-estrella-supermasiva-nuevo-tipo-supernova_14626

Astrónomos descubren un nuevo tipo de supernova jamás antes observada, capaz de arrasar por completo con su estrella madre, y que puede representar la forma en la que mueren las estrella más masivas del universo, incluidas las primeras estrellas.

Supernova SN2016iet

Foto: Gemini Observatory/NSF/AURA/ Ilustración: Joy Pollard

Héctor Rodríguez

El satélite Gaia de la Agencia Espacial Europea -ESA- detectó por primera vez la supernova conocida como SN 2016iet

el 14 de noviembre de 2016. Desde este momento se sucedieron tres años

de intensas observaciones de seguimiento con una gran variedad de

telescopios, entre los que se incluyo el telescopio Gemini North situado en Maunakea, Hawai, y el cual proporcionó los datos cruciales sobre la distancia y composición del objeto.

"Los datos de Gemini nos permitieron estudiar SN 2016iet más de 800

días después de su descubrimiento, cuando ya se había atenuado a la

centésima parte de su brillo máximo", explica Edo Berger del Centro Harvard-Smithsonian de Astrofísica.

Un nuevo tipo de supernova que puede aniquilar por completo a su estrella madre sin dejar ningún remanente

Chris Davis, director del programa de la National Science Foundation -NSF-

añade: “estas observaciones de Gemini demuestran la importancia de

estudiar el universo en constante cambio. Buscar en el cielo eventos

explosivos repentinos, observarlos rápidamente y, lo que es más

importante, poder monitorearlos durante días, semanas, meses y, a veces,

incluso años es fundamental para obtener una visión global de este tipo

de fenómenos".

Una supernova única

En este caso, la mirada profunda de Gemini reveló una débil emisión

de hidrógeno en la ubicación de la supernova, evidencia de que la estrella

progenitora de SN 2016iet vivía en una región aislada con muy poca

formación de estrellas; un ambiente inusual para una estrella tan

masiva. "A pesar de buscar durante décadas entre miles de

supernovas, esta es diferente a cualquier cosa que hayamos visto antes. A

veces vemos supernovas que son inusuales en un aspecto, pero que por lo

demás son normales; esta es única en todos los sentidos posibles"

explica Davis. 7

"Esta supernova es única en todos los sentidos posibles"

Así, SN 2016iet tiene multitud de rarezas, incluida su

increíblemente larga duración, una gran energía, huellas químicas

inusuales y un entorno pobre en elementos más pesados, para lo cual no

existen análogos obvios en la literatura astronómica. "Cuando

nos dimos cuenta por primera vez de lo inusual que es SN 2016iet, mi

reacción fue: ´¿Algo ha salido terriblemente mal con nuestros datos?´,

declara Sebastián Gómez, también

del Centro de Astrofísica de la Universidad de Harvard y autor

principal de la investigación publicada en la revista especializada The Astrophysical Journal.

Estrellas supermasivas, estrellas primordiales y las supernovas de inestabilidad de pares

La naturaleza inusual de SN 2016iet, según lo revelado por Gemini y

los datos de otros satélites, sugiere que comenzó su vida como una

estrella con aproximadamente 200 veces la masa de nuestro Sol, por lo

que es una de las explosiones de estrellas individuales más masivas y poderosas jamás observadas. La

creciente evidencia sugiere que las primeras estrellas nacidas en el

universo pueden haber sido igual de masivas. Los astrónomos predijeron

que si tales gigantes conservan su masa durante su breve vida -unos

pocos millones de años- morirán como supernovas de inestabilidad de pares, las cuales reciben su nombre de los pares de materia-antimateria formados en la explosión.

Las supernovas de inestabilidad de pares reciben su nombre de los pares de materia-antimateria formados en la explosión

La mayoría de las estrellas masivas terminan sus vidas en una supernova que arroja materia rica en metales pesados al espacio, mientras que su núcleo se convierte en una estrella de neutrones o un agujero negro.

No obstante, las supernovas de inestabilidad de pares actúan de manera

diferente. En ellas el núcleo al colapsar produce abundante radiación de

rayos gamma, lo que conduce a una producción desbocada de pares de

partículas y antipartículas que desencadenan una explosión termonuclear

catastrófica que aniquila a toda la estrella, incluido el núcleo.

Los modelos de supernovas de inestabilidad de pares predicen que estas ocurrirán en entornos pobres en metales -término astronómico empleado para los elementos más pesados que el hidrógeno y el helio- como galaxias enanas o el universo temprano

que es exactamente lo que el equipo de Gómez encontró en su

investigación. . El fenómeno ocurrió a una distancia de aproximadamente

mil millones de años luz de distancia en una galaxia enana previamente

no catalogada pobre en metales. "Esta es la primera supernova en la que

el contenido de masa y metal de la estrella en explosión está en el

rango predicho por los modelos teóricos", afirma el investigador.

En la soledad del cosmos

Otra característica sorprendente es la ubicación austera de SN

2016iet. La mayoría de las estrellas masivas nacen en densos cúmulos de

estrellas, pero SN 2016iet se formó de forma aislada a unos 54.000 años luz de distancia del centro de su galaxia enana.

"Cómo se puede formar una estrella tan masiva en completo aislamiento

sigue siendo un misterio", explica Gómez. "En nuestro vecindario cósmico

local, solo conocemos algunas estrellas que se acercan a la masa de la

estrella que explotó en SN 2016iet, pero todas ellas viven en cúmulos

masivos con miles de otras estrellas", añade.

"Cómo se puede formar una estrella tan masiva en completo aislamiento sigue siendo un misterio"

Para explicar la larga duración de la supernova y la lenta evolución su brillo, el equipo postula que la

estrella progenitora expulsó su propia materia al entorno circundante a

una tasa de aproximadamente tres veces la masa del Sol por año durante

una década antes de que esta se volviera inestable. Cuando la

estrella finalmente explotó, los escombros de la supernova chocaron con

este material que alimentaba la emisión de SN 2016iet.

“La mayoría de las supernovas se desvanecen y se vuelven invisibles

contra el resplandor de sus galaxias anfitrionas en unos pocos meses.

Pero debido a que SN 2016iet era tan brillante y tan aislada, pudimos

estudiar su evolución en los años venideros ”, continúa el astrónomo.

"La idea de las supernovas de inestabilidad de pares ha existido

durante décadas", afirma Berger por su parte, "pero finalmente tener el

primer ejemplo de observación que coloca a una estrella moribunda en el

régimen de masa correcto, con el comportamiento correcto y en una

galaxia enana pobre en metales, es un increíble paso adelante".

Hasta hace muy poco tiempo, no se sabía si tales estrellas supermasivas podrían existir realmente.

El descubrimiento y las observaciones de seguimiento de SN 2016iet han

proporcionado pruebas claras de su existencia y de su potencial para

afectar el desarrollo del universo temprano. "El papel de Gémini en este

sorprendente descubrimiento es muy significativo", afirma Gómez, "ya

que nos ayuda a comprender mejor cómo se desarrolló el universo

primitivo después de sus 'edades oscuras', -cuando todavía no existían

estrellas en el firmamento- hasta convertirse en el esplendoroso

universo que podemos observar hoy", concluye.

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

Guillermo Gonzalo Sánchez Achutegui

Inscríbete en el Foro del blog y participa : A Vuelo De Un Quinde - El Foro!

Figure 1. Artist’s concept of the SN 2016iet pair-instability

supernova. Credit: Gemini Observatory/NSF/AURA/ illustration by Joy

Pollard

Figure 1. Artist’s concept of the SN 2016iet pair-instability

supernova. Credit: Gemini Observatory/NSF/AURA/ illustration by Joy

Pollard

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario

Por favor deja tus opiniones, comentarios y/o sugerencias para que nosotros podamos mejorar cada día. Gracias !!!.