Hola amigos: A VUELO DE UN QUINDE EL BLOG., la agencia espacial norteamericana NASA, logró con éxito el aterrizaje(amartizaje) del Robot InSight en Elysium Planitia en el Planeta Marte; el 26 de noviembre del 2018.

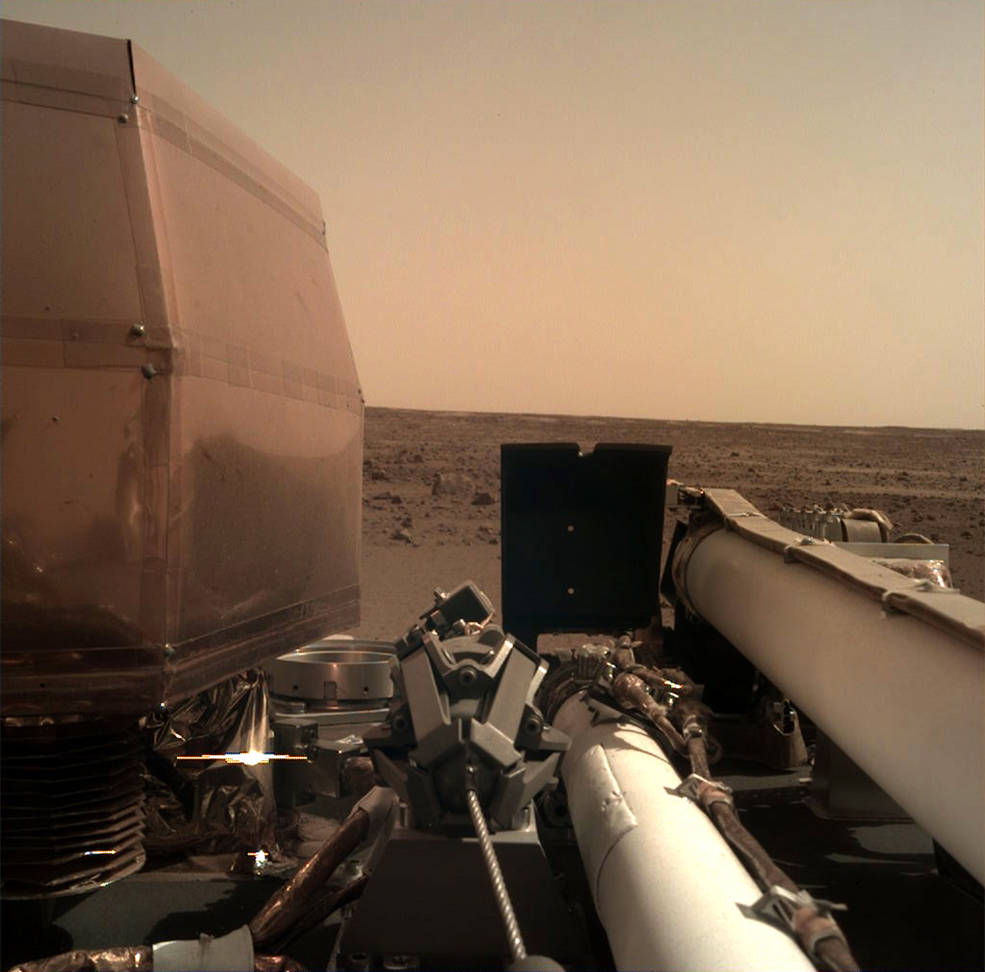

NASA .- narró : El aterrizador InSight de la NASA ha enviado señales a la Tierra indicando que sus paneles solares están abiertos y que recogen luz solar en la superficie marciana. La sonda espacial Mars Odyssey de la NASA transmitió las señales que se recibieron en la Tierra aproximadamente a la 1:30 GMT de la madrugada del martes 27 de Noviembre. El despliegue de los paneles solares garantiza que la nave pueda recargar sus baterías cada día. Odyssey también transmitió un par de imágenes que muestran el lugar del aterrizaje de InSight.

"El equipo de InSight puede descansar un poco más fácil esta noche ahora que sabemos que los paneles solares de la nave espacial están desplegados y recargando las baterías", dijo Tom Hoffman, gerente del proyecto InSight en el Laboratorio de Propulsión a Chorro de la NASA en Pasadena, California, que lidera la misión. "Ha sido un día largo para el equipo. Pero mañana comienza un nuevo y emocionante capítulo para InSight: operaciones de superficie y el comienzo de la fase de implementación del instrumento..."

InSight es la NASA robotic lander diseñado para estudiar el interior del planet Mars. La misionera lanzada el 5 de mayo de 2018 a las 11:05 UTC y se espera que sea de tierra en la superficie de Mars a Elysium Planitia el 26 de noviembre de 2018. ESA ha apoyado la misión desde que fue lanzada, En el caso de que se produzca un error en el sistema operativo, se debe tener en cuenta que el sistema operativo no es compatible con el sistema operativo.

http://www.esa.int/spaceinimages/Images/2018/11/NASA_s_InSight_lander_operating_on_the_surface_of_MarsESA

InSight Aterriza con Éxito en Marte y Despliega sus Paneles Solares

|

| La Cámara de Implementación de Instrumentos (IDC), ubicada en el brazo robot de InSight, tomó esta fotografía de la superficie marciana el 26 de Noviembre de 2018, el mismo día en que la nave espacial aterrizó en el Planeta Rojo. La cubierta transparente para el polvo de la cámara aún está en esta imagen, para evitar que las partículas levantadas durante el aterrizaje se asienten en la lente de la cámara. Esta imagen fue transmitida desde InSight a la Tierra a través de la nave espacial Odyssey de la NASA, actualmente en órbita alrededor de Marte. Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech |

El aterrizador InSight de la NASA ha enviado señales a la Tierra indicando que sus paneles solares están abiertos y que recogen luz solar en la superficie marciana. La sonda espacial Mars Odyssey de la NASA transmitió las señales que se recibieron en la Tierra aproximadamente a la 1:30 GMT de la madrugada del martes 27 de Noviembre. El despliegue de los paneles solares garantiza que la nave pueda recargar sus baterías cada día. Odyssey también transmitió un par de imágenes que muestran el lugar del aterrizaje de InSight.

"El equipo de InSight puede descansar un poco más fácil esta noche ahora que sabemos que los paneles solares de la nave espacial están desplegados y recargando las baterías", dijo Tom Hoffman, gerente del proyecto InSight en el Laboratorio de Propulsión a Chorro de la NASA en Pasadena, California, que lidera la misión. "Ha sido un día largo para el equipo. Pero mañana comienza un nuevo y emocionante capítulo para InSight: operaciones de superficie y el comienzo de la fase de implementación del instrumento".

Los paneles solares gemelos de InSight tienen 2,2 metros de ancho; cuando están abiertos, todo el módulo de aterrizaje tiene aproximadamente el tamaño de un coche convertible grande de la década de 1960. Marte tiene una luz solar más débil que la Tierra porque está mucho más lejos del Sol. Pero el módulo de aterrizaje no necesita mucho para operar: los paneles proporcionan de 600 a 700 vatios en un día claro, suficiente para alimentar una licuadora doméstica y mucho para mantener a sus instrumentos dirigiendo la ciencia en el Planeta Rojo. Incluso cuando el polvo cubra los paneles, lo que es probable que ocurra con frecuencia en Marte, deberían poder proporcionar al menos de 200 a 300 vatios.

Los paneles están inspirados en aquellos utilizados con el Phoenix Mars Lander de la NASA, aunque los de InSight son un poco más grandes para proporcionar más potencia y aumentar su resistencia estructural. Estos cambios fueron necesarios para apoyar las operaciones durante un año completo en Marte (dos años terrestres).

En los próximos días, el equipo de la misión desarmará el brazo robótico de InSight y usará la cámara adjunta para tomar fotos del suelo para que los ingenieros puedan decidir dónde colocar los instrumentos científicos de la nave espacial. Pasarán de dos a tres meses antes de que esos instrumentos se implementen por completo y envíen datos.

Mientras tanto, InSight utilizará sus sensores meteorológicos y magnetómetro para tomar lecturas de su lugar de aterrizaje en Elysium Planitia, su nuevo hogar en Marte.

Todo Listo Para la Llegada a Marte de la Misión InSight el Próximo Lunes

|

| Concepto artístico de la reentrada de InSight en la atmósfera de Marte. Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech |

La nave espacial InSight va por buen camino para un aterrizaje suave en la superficie del Planeta Rojo el 26 de Noviembre, el lunes después del Día de Acción de Gracias. Pero no será un fin de semana relajante con sobras de pavo, fútbol y compras para el equipo de la misión de InSight. Los ingenieros estarán atentos al flujo de datos que indican la salud y trayectoria de InSight, y monitorearán los informes meteorológicos marcianos para determinar si el equipo necesita realizar algún ajuste final en la preparación para el aterrizaje, a solo unos días.

"Llegar a Marte es difícil. Requiere habilidad, enfoque y años de preparación", dijo Thomas Zurbuchen, administrador asociado de la Dirección de Misiones Científicas en la sede de la NASA en Washington. "Teniendo en cuenta nuestro ambicioso objetivo de enviar a los humanos a la superficie de la Luna y luego a Marte, sé que nuestro increíble equipo de ciencia e ingeniería, el único en el mundo que ha aterrizado con éxito una nave espacial en la superficie marciana, hará todo lo que pueda. Puede aterrizar con éxito InSight en el Planeta Rojo ".

InSight, la primera misión para estudiar el interior profundo de Marte, despegó desde la Base de la Fuerza Aérea de Vandenberg en el centro de California el 5 de Mayo de 2018. Ha sido un vuelo sin incidentes a Marte, y los ingenieros lo aprecian así. Tendrán mucha emoción cuando InSight llegue a la cima de la atmósfera marciana a 19.800 kilómetros por hora y reduzca la velocidad a 8 kilómetros por hora, antes de que sus tres patas toquen el suelo marciano. Esa desaceleración extrema tiene que suceder en poco menos de siete minutos. Tras esos siete minutos de descenso atravesando la peligrosa atmósfera de Marte, InSight tocará suelo marciano el lunes sobre las 20:00 GMT.

"Hay una razón por la que los ingenieros llaman el aterrizaje los siete minutos del terror de Marte", dijo Rob Grover, líder de entrada, descenso y aterrizaje (EDL) de InSight, con sede en el Laboratorio de Propulsión a Chorro de la NASA en Pasadena, California. "No podemos usar el joystick para el aterrizaje, por lo que tenemos que confiar en los comandos que pre-programamos en la nave. Hemos pasado años probando nuestros planes, aprendiendo de otros aterrizajes de Marte y estudiando todas las condiciones que Marte puede ofrecernos. Y nos mantendremos atentos hasta que InSight se establezca en su hogar en la región de Elysium Planitia ".

Una forma en que los ingenieros pueden confirmar rápidamente las actividades que InSight ha completado durante esos siete minutos de terror es si la misión experimental de CubeSat conocida como Mars Cube One (MarCO) transmite datos de InSight a la Tierra casi en tiempo real durante su sobrevuelo el 26 de Noviembre. Las dos naves espaciales MarCO (A y B) están progresando hacia su punto de encuentro, y sus radios ya han pasado sus primeras pruebas en el espacio profundo.

"Solo sobreviviendo al viaje hasta el momento, los dos satélites MarCO han dado un gran salto para los CubeSats", dijo Anne Marinan, ingeniera de sistemas de MarCO con sede en JPL. "Y ahora nos estamos preparando para la próxima prueba de las MarCO: servir como un posible modelo para un nuevo tipo de retransmisión de comunicaciones interplanetarias".

Si todo va bien, los MarCO pueden tardar unos segundos en recibir y formatear los datos antes de enviarlos a la Tierra a la velocidad de la luz. Esto significaría que los ingenieros de JPL y otro equipo de Lockheed Martin Space en Denver podrían decir lo que hizo el módulo de aterrizaje durante el EDL aproximadamente ocho minutos después de que InSight complete sus actividades. Sin MarCO, el equipo de InSight tendría que esperar varias horas para que los datos de ingeniería regresen a través de las vías de comunicación principales: los relevos a través de las sondas espaciales MRO y Odyssey de la NASA en Marte.

Una vez que los ingenieros sepan que la nave espacial ha aterrizado de manera segura en una de las varias formas en que tienen que confirmar este hito y que los paneles solares de InSight se han desplegado correctamente, el equipo puede instalarse en el proceso cuidadoso de tres meses de implementación de instrumentos científicos.

"Aterrizar en Marte es emocionante, pero los científicos esperan con ansias el momento después de que InSight aterrice", dijo Lori Glaze, directora en funciones de la División de Ciencia Planetaria en la sede de la NASA. "Una vez que InSight se haya establecido en el Planeta Rojo y se hayan desplegado sus instrumentos, comenzará a recopilar información valiosa sobre la estructura del interior profundo de Marte, información que nos ayudará a comprender la formación y evolución de todos los planetas rocosos, incluido el que llamamos casa."

"Las misiones anteriores no han sido tan profundas en Marte", agregó Sue Smrekar, investigadora principal adjunta de la misión InSight en JPL. "Los científicos de InSight no pueden esperar para explorar el corazón de Marte".

|

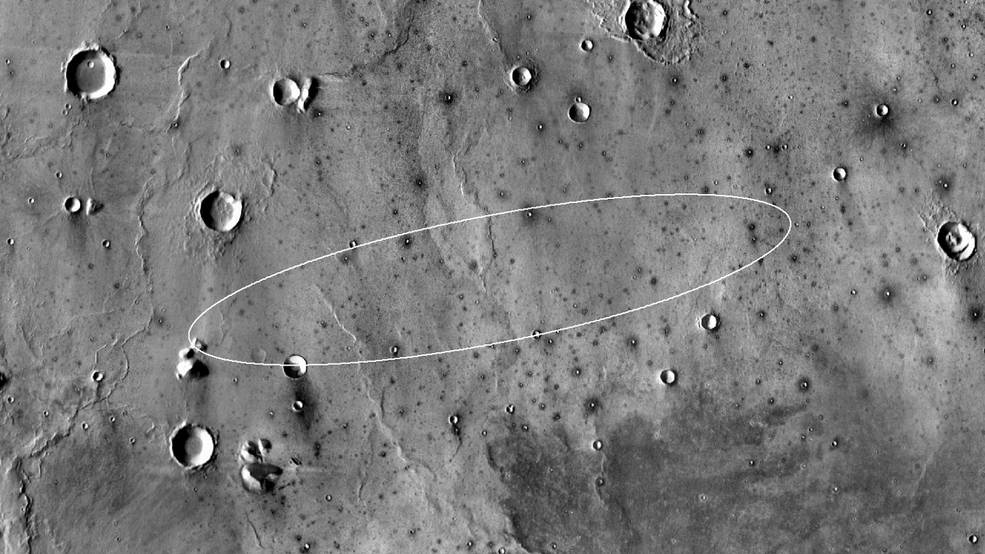

| La sonda espacial Mars Odyssey tomó esta imagen de la zona de aterrizaje de InSight. Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech |

NASA InSight Team on Course for Mars Touchdow

An artist's impression of NASA InSight's entry, descent and landing at Mars, scheduled for Nov. 26, 2018.

Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech

NASA's Mars Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport (InSight) spacecraft is on track for a soft touchdown on the surface of the Red Planet on Nov. 26, the Monday after Thanksgiving. But it's not going to be a relaxing weekend of turkey leftovers, football and shopping for the InSight mission team. Engineers will be keeping a close eye on the stream of data indicating InSight's health and trajectory, and monitoring Martian weather reports to figure out if the team needs to make any final adjustments in preparation for landing, only five days away.

"Landing on Mars is hard. It takes skill, focus and years of preparation," said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for the Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington. "Keeping in mind our ambitious goal to eventually send humans to the surface of the Moon and then Mars, I know that our incredible science and engineering team — the only in the world to have successfully landed spacecraft on the Martian surface — will do everything they can to successfully land InSight on the Red Planet."

InSight, the first mission to study the deep interior of Mars, blasted off from Vandenberg Air Force Base in Central California on May 5, 2018. It has been an uneventful flight to Mars, and engineers like it that way. They will get plenty of excitement when InSight hits the top of the Martian atmosphere at 12,300 mph (19,800 kph) and slows down to 5 mph (8 kph) — about human jogging speed — before its three legs touch down on Martian soil. That extreme deceleration has to happen in just under seven minutes.

This artist's illustration shows NASA's four successful Mars rovers (from left to right): Sojourner, Spirit and Opportunity, and Curiosity. The image also shows the upcoming Mars 2020 rover and a human explorer.

Credits: NASA

"There's a reason engineers call landing on Mars 'seven minutes of terror,'" said Rob Grover, InSight's entry, descent and landing (EDL) lead, based at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. "We can't joystick the landing, so we have to rely on the commands we pre-program into the spacecraft. We've spent years testing our plans, learning from other Mars landings and studying all the conditions Mars can throw at us. And we're going to stay vigilant till InSight settles into its home in the Elysium Planitia region."

One way engineers may be able to confirm quickly what activities InSight has completed during those seven minutes of terror is if the experimental CubeSat mission known as Mars Cube One (MarCO) relays InSight data back to Earth in near-real time during their flyby on Nov. 26. The two MarCO spacecraft (A and B) are making good progress toward their rendezvous point, and their radios have already passed their first deep-space tests.

NASA Science missions circle Earth, the Sun, the Moon, Mars and many other destinations within our solar system, including spacecraft that look out even further into our universe. The Science Fleet depicts the scope of NASA's activity and how our missions have traveled throughout the solar system.

Credits: NASA/GSFC

"Just by surviving the trip so far, the two MarCO satellites have made a giant leap for CubeSats," said Anne Marinan, a MarCO systems engineer based at JPL. "And now we are gearing up for the MarCOs' next test — serving as a possible model for a new kind of interplanetary communications relay."

If all goes well, the MarCOs may take a few seconds to receive and format the data before sending it back to Earth at the speed of light. This would mean engineers at JPL and another team at Lockheed Martin Space in Denver would be able to tell what the lander did during EDL approximately eight minutes after InSight completes its activities. Without MarCO, InSight's team would need to wait several hours for engineering data to return via the primary communications pathways — relays through NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and Mars Odyssey orbiter.

This map shows the temperature of the Martian atmosphere 16 miles above the surface. The data were taken on Nov. 18, 2018, by NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, about one week before NASA's InSight lander is scheduled to touchdown on the Martian surface. The temperature indicates to mission scientists the amount of dust activity in the atmosphere. The map shows a range of latitudes, with temperatures clearly dropping near the planet's north pole. The landing locations of various NASA Mars landers are shown for context.

Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Once engineers know that the spacecraft has touched down safely in one of the several ways they have to confirm this milestone and that InSight's solar arrays have deployed properly, the team can settle into the careful, three-month-long process of deploying science instruments.

"Landing on Mars is exciting, but scientists are looking forward to the time after InSight lands," said Lori Glaze, acting director of the Planetary Science Division at NASA Headquarters. "Once InSight is settled on the Red Planet and its instruments are deployed, it will start collecting valuable information about the structure of Mars' deep interior — information that will help us understand the formation and evolution of all rocky planets, including the one we call home."

This artist’s concept depicts the smooth, flat ground that dominates InSight's landing ellipse in the Elysium Planitia region of Mars.

Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech

"Previous missions haven't gone more than skin-deep at Mars," added Sue Smrekar, the InSight mission's deputy principal investigator at JPL. "InSight scientists can’t wait to explore the heart of Mars."

The Mars Odyssey orbiter took this image of the target landing site for NASA's InSight lander.

Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASU

JPL manages InSight for NASA's Science Mission Directorate. InSight is part of NASA's Discovery Program, managed by the agency's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. Lockheed Martin Space in Denver built the InSight spacecraft, including its cruise stage and lander, and supports spacecraft operations for the mission.

The artist's impression shows the major interior layers of Earth, Mars and the Moon.

Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech

A number of European partners, including France's Centre National d'Études Spatiales (CNES) and the German Aerospace Center (DLR), are supporting the InSight mission. CNES and the Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris (IPGP) provided the Seismic Experiment for Interior Structure (SEIS) instrument, with significant contributions from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) in Germany, the Swiss Institute of Technology (ETH) in Switzerland, Imperial College and Oxford University in the United Kingdom, and JPL. DLR provided the Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package (HP3) instrument, with significant contributions from the Space Research Center (CBK) of the Polish Academy of Sciences and Astronika in Poland. Spain’s Centro de Astrobiología (CAB) supplied the wind sensors.

NASA's InSight Mars Lander in fully landed configuration in the clean room at Lockheed Martin Space in Littleton, Colorado. Once the solar arrays are fully deployed on Mars, they can provide 600-700 watts on a clear day, or just enough to power a household blender.

Credits: Lockheed Martin

For more detailed information on the InSight mission, visit:

For more information about MarCO, visit:

Jia-Rui Cook / D.C. Agle

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

818-354-5011

jccook@jpl.nasa.gov / agle@jpl.nasa.gov

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

818-354-5011

jccook@jpl.nasa.gov / agle@jpl.nasa.gov

Dwayne Brown / JoAnna Wendel

Headquarters, Washington

202-358-1726 / 202-358-1003

dwayne.c.brown@nasa.gov / joanna.r.wendel@nasa.gov

Headquarters, Washington

202-358-1726 / 202-358-1003

dwayne.c.brown@nasa.gov / joanna.r.wendel@nasa.gov

2018-272

Last Updated: Nov. 26, 2018

Editor: Tony Greicius

Read Next Related Article

NASA InSight Landing on Mars: Milestones

This illustration shows a simulated view of NASA's InSight lander descending on its parachute toward the surface of Mars.

Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech

On Nov. 26, NASA's InSight spacecraft will blaze through the Martian atmosphere and attempt to set a lander gently on the surface of the Red Planet in less time than it takes to hard-boil an egg. InSight's entry, descent and landing (EDL) team, based at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, along with another part of the team at Lockheed Martin Space in Denver, have pre-programmed the spacecraft to perform a specific sequence of activities to make this possible.

The following is a list of expected milestones for the spacecraft, assuming all proceeds exactly as planned and engineers make no final changes the morning of landing day. Some milestones will be known quickly only if the experimental Mars Cube One (MarCO) spacecraft are providing a reliable communications relay from InSight back to Earth. The primary communications path for InSight engineering data during the landing process is through NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and Mars Odyssey. Those data are expected to become available several hours after landing.

If all goes well, MarCO may take a few seconds to receive and format the data before sending it back to Earth at the speed of light. The one-way time for a signal to reach Earth from Mars is eight minutes and seven seconds on Nov. 26. Times listed below are in Earth Receive Time, or the time JPL Mission Control may receive the signals relating to these activities.

- 11:40 a.m. PST (2:40 p.m. EST) — Separation from the cruise stage that carried the mission to Mars

- 11:41 a.m. PST (2:41 p.m. EST) — Turn to orient the spacecraft properly for atmospheric entry

- 11:47 a.m. PST (2:47 p.m. EST) — Atmospheric entry at about 12,300 mph (19,800 kph), beginning the entry, descent and landing phase

- 11:49 a.m. PST (2:49 p.m. EST) — Peak heating of the protective heat shield reaches about 2,700°F (about 1,500°C)

- 15 seconds later — Peak deceleration, with the intense heating causing possible temporary dropouts in radio signals

- 11:51 a.m. PST (2:51 p.m. EST) — Parachute deployment

- 15 seconds later — Separation from the heat shield

- 10 seconds later — Deployment of the lander's three legs

- 11:52 a.m. PST (2:52 p.m. EST) — Activation of the radar that will sense the distance to the ground

- 11:53 a.m. PST (2:53 p.m. EST) — First acquisition of the radar signal

- 20 seconds later — Separation from the back shell and parachute

- 0.5 second later — The retrorockets, or descent engines, begin firing

- 2.5 seconds later — Start of the "gravity turn" to get the lander into the proper orientation for landing

- 22 seconds later — InSight begins slowing to a constant velocity (from 17 mph to a constant 5 mph, or from 27 kph to 8 kph) for its soft landing

- 11:54 a.m. PST (2:54 p.m. EST) — Expected touchdown on the surface of Mars

- 12:01 p.m. PST (3:01 p.m. EST) — "Beep" from InSight's X-band radio directly back to Earth, indicating InSight is alive and functioning on the surface of Mars

- No earlier than 12:04 p.m. PST (3:04 p.m. EST), but possibly the next day — First image from InSight on the surface of Mars

- No earlier than 5:35 p.m. PST (8:35 p.m. EST) — Confirmation from InSight via NASA's Mars Odyssey orbiter that InSight's solar arrays have deployed

For the latest updates on InSight’s status, visit:

The InSight press kit, with additional information about the mission time line, is available at:

JPL manages InSight for NASA's Science Mission Directorate. InSight is part of NASA's Discovery Program, managed by the agency's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. Lockheed Martin Space in Denver built the InSight spacecraft, including its cruise stage and lander, and supports spacecraft operations for the mission.

A number of European partners, including France's Centre National d'Études Spatiales (CNES) and the German Aerospace Center (DLR), are supporting the InSight mission. CNES provided the Seismic Experiment for Interior Structure (SEIS) instrument, with significant contributions from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) in Germany, the Swiss Institute of Technology (ETH) in Switzerland, Imperial College and Oxford University in the United Kingdom, and JPL. DLR provided the Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package (HP3) instrument, with significant contributions from the Space Research Center (CBK) of the Polish Academy of Sciences and Astronika in Poland. Spain’s Centro de Astrobiología (CAB) supplied the wind sensors.

For more information about InSight, visit:

InSight's success does not depend on MarCO being able to relay communications. Additional information about how InSight will communicate during entry, descent and landing is available here. JPL, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages MarCO for NASA's Science Mission Directorate in Washington.

Jia-Rui Cook / Andrew Good

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

818-354-5011

jccook@jpl.nasa.gov / andrew.c.good@jpl.nasa.gov

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

818-354-5011

jccook@jpl.nasa.gov / andrew.c.good@jpl.nasa.gov

Dwayne Brown / JoAnna Wendel

NASA Headquarters, Washington

202-358-1726 / 202-358-1003

dwayne.c.brown@nasa.gov / joanna.r.wendel@nasa.gov

NASA Headquarters, Washington

202-358-1726 / 202-358-1003

dwayne.c.brown@nasa.gov / joanna.r.wendel@nasa.gov

2018-273

Last Updated: Nov. 21, 2018

Editor: Tony Greicius

Mars New Home 'a Large Sandbox'

NASA’s InSight spacecraft popped the lens cover off its Instrument Context Camera (ICC) on Nov. 30, 2018, and captured this view of Mars. Located below the deck of the InSight lander, the ICC has a fisheye view, creating a curved horizon. Some clumps of dust are visible on the camera’s lens. One of the spacecraft’s footpads can be seen in the lower right corner. The seismometer’s tether box is in the upper left corner.

Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech

With InSight safely on the surface of Mars, the mission team at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, is busy learning more about the spacecraft's landing site. They knew when InSight landed on Nov. 26 that the spacecraft had touched down on target, a lava plain named Elysium Planitia. Now they've determined that the vehicle sits slightly tilted (about 4 degrees) in a shallow dust- and sand-filled impact crater known as a "hollow." InSight has been engineered to operate on a surface with an inclination up to 15 degrees.

"The science team had been hoping to land in a sandy area with few rocks since we chose the landing site, so we couldn't be happier," said InSight project manager Tom Hoffman of JPL. "There are no landing pads or runways on Mars, so coming down in an area that is basically a large sandbox without any large rocks should make instrument deployment easier and provide a great place for our mole to start burrowing."

Rockiness and slope grade factor into landing safety and are also important in determining whether InSight can succeed in its mission after landing. Rocks and slopes could affect InSight's ability to place its heat-flow probe — also known as "the mole," or HP3 — and ultra-sensitive seismometer, known as SEIS, on the surface of Mars.

As visible in this two-frame set of images, NASA’s InSight spacecraft unlatched its robotic arm on Nov. 27, 2018, the day after it landed on Mars.

Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Touching down on an overly steep slope in the wrong direction could also have jeopardized the spacecraft's ability to get adequate power output from its two solar arrays, while landing beside a large rock could have prevented InSight from being able to open one of those arrays. In fact, both arrays fully deployed shortly after landing.

The InSight science team's preliminary assessment of the photographs taken so far of the landing area suggests the area in the immediate vicinity of the lander is populated by only a few rocks. Higher-resolution images are expected to begin arriving over the coming days, after InSight releases the clear-plastic dust covers that kept the optics of the spacecraft's two cameras safe during landing.

"We are looking forward to higher-definition pictures to confirm this preliminary assessment," said JPL's Bruce Banerdt, principal investigator of InSight. "If these few images — with resolution-reducing dust covers on — are accurate, it bodes well for both instrument deployment and the mole penetration of our subsurface heat-flow experiment."

Once sites on the Martian surface have been carefully selected for the two main instruments, the team will unstow and begin initial testing of the mechanical arm that will place them there.

Data downlinked from the lander also indicate that during its first full day on Mars, the solar-powered InSight spacecraft generated more electrical power than any previous vehicle on the surface of Mars.

"It is great to get our first 'off-world record' on our very first full day on Mars," said Hoffman. "But even better than the achievement of generating more electricity than any mission before us is what it represents for performing our upcoming engineering tasks. The 4,588 watt-hours we produced during sol 1 means we currently have more than enough juice to perform these tasks and move forward with our science mission."

Launched from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California May 5, InSight will operate on the surface for one Martian year, plus 40 Martian days, or sols — the equivalent of nearly two Earth years. InSight will study the deep interior of Mars to learn how all celestial bodies with rocky surfaces, including Earth and the Moon, formed.

JPL manages InSight for NASA's Science Mission Directorate. InSight is part of NASA's Discovery Program, managed by the agency's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama.

A number of European partners, including France's Centre National d'Études Spatiales (CNES) and the German Aerospace Center (DLR), are supporting the InSight mission. CNES, and the Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris (IPGP), provided the SEIS instrument, with significant contributions from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) in Germany, the Swiss Institute of Technology (ETH) in Switzerland, Imperial College and Oxford University in the United Kingdom, and JPL. DLR provided the HP3 instrument, with significant contributions from the Space Research Center (CBK) of the Polish Academy of Sciences and Astronika in Poland. Spain's Centro de Astrobiología (CAB) supplied the wind sensors.

For more information about InSight, visit:

For more information about NASA's Mars missions, go to:

Dwayne Brown / JoAnna Wendel

NASA Headquarters, Washington

202-358-1726 / 202-358-1003

dwayne.c.brown@nasa.gov / joanna.r.wendel@nasa.gov

NASA Headquarters, Washington

202-358-1726 / 202-358-1003

dwayne.c.brown@nasa.gov / joanna.r.wendel@nasa.gov

2018-278

Last Updated: Nov. 30, 2018

Editor: Tony Greicius

The Mars InSight Landing Site Is Just Plain Perfect

This artist’s concept depicts the smooth, flat ground that dominates InSight's landing ellipse in the Elysium Planitia region of Mars.

Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech

No doubt about it, NASA explores some of the most awe-inspiring locations in our solar system and beyond. Once seen, who can forget the majesty of astronaut Jim Irwin standing before the stark beauty of the Moon's Hadley Apennine mountain range, of the Hubble Space Telescope's gorgeous "Pillars of Creation" or Cassini's magnificent mosaic of Saturn?

Mars also plays a part in this visually compelling equation, with the high-definition imagery from the Curiosity rover of the ridges and rounded buttes at the base of Mount Sharp bringing to mind the majesty of the American Southwest. That said, Elysium Planitia – the site chosen for the Nov. 26 landing of NASA's InSight mission to Mars – will more than likely never be mentioned with those above because it is, well, plain.

"If Elysium Planitia were a salad, it would consist of romaine lettuce and kale – no dressing," said InSight principal investigator Bruce Banerdt at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. "If it were an ice cream, it would be vanilla."

Yes, the landing site of NASA's next Mars mission may very well look like a stadium parking lot, but that is the way the Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport (InSight) project likes it.

"Previous missions to the Red Planet have investigated its surface by studying its canyons, volcanoes, rocks and soil," said Banerdt. "But the signatures of the planet's formation processes can be found only by sensing and studying evidence buried far below the surface. It is InSight's job to study the deep interior of Mars, taking the planet's vital signs – its pulse, temperature and reflexes."

Taking those vital signs will help the InSight science team look back to a time when the rocky planets of the solar system formed. The investigations will depend on three instruments:

A six-sensor seismometer called the Seismic Experiment for Interior Structure (SEIS) will record seismic waves traveling through the interior structure of the planet. Studying seismic waves will tell scientists what might be creating the waves. (On Mars, scientists suspect that the culprits may be marsquakes or meteorites striking the surface.)

The mission's Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package (HP3) will burrow deeper than any other scoop, drill or probe on Mars before to gauge how much heat is flowing out of the planet. Its observations will shed light on whether Earth and Mars are made of the same stuff.

Finally, InSight's Rotation and Interior Structure Experiment (RISE) experiment will use the lander's radios to assess the wobble of Mars' rotation axis, providing information about the planet's core.

For InSight to do its work, the team needed a landing site that checked off several boxes, because as a three-legged lander – not a rover – InSight will remain wherever it touches down.

The landing site for InSight, in relation to landing sites for seven previous missions, is shown on a topographic map of Mars.

Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech

"Picking a good landing site on Mars is a lot like picking a good home: It's all about location, location, location," said Tom Hoffman, InSight project manager at JPL. "And for the first time ever, the evaluation for a Mars landing site had to consider what lay below the surface of Mars. We needed not just a safe place to land, but also a workspace that's penetrable by our 16-foot-long (5-meter) heat-flow probe."

The site also needs to be bright enough and warm enough to power the solar cells while keeping its electronics within temperature limits for an entire Martian year (26 Earth months).

So the team focused on a band around the equator, where the lander's solar array would have adequate sunlight to power its systems year-round. Finding an area that would be safe enough for InSight to land and then deploy its solar panels and instruments without obstructions took a little longer.

"The site has to be a low-enough elevation to have sufficient atmosphere above it for a safe landing, because the spacecraft will rely first on atmospheric friction with its heat shield and then on a parachute digging into Mars' tenuous atmosphere for a large portion of its deceleration," said Hoffman. "And after the chute has fallen away and the braking rockets have kicked in for final descent, there needs to be a flat expanse to land on – not too undulating and relatively free of rocks that could tip the tri-legged Mars lander."

Of 22 sites considered, only Elysium Planitia, Isidis Planitia and Valles Marineris met the basic engineering constraints. To grade the three remaining contenders, reconnaissance images from NASA's Mars orbiters were scoured and weather records searched. Eventually, Isidis Planitia and Valles Marineris were ruled out for being too rocky and windy.

That left the 81-mile long, 17-mile-wide (130-kilometer-long, 27-kilometer-wide) landing ellipse on the western edge of a flat, smooth expanse of lava plain.

"If you were a Martian coming to explore Earth's interior like we are exploring Mars' interior, it wouldn't matter if you put down in the middle of Kansas or the beaches of Oahu," said Banerdt. "While I'm looking forward to those first images from the surface, I am even more eager to see the first data sets revealing what is happening deep below our landing pads. The beauty of this mission is happening below the surface. Elysium Planitia is perfect."

This map shows the single area under continuing evaluation as the InSight mission's Mars landing site, as of a year before the mission's May 2016 launch. The finalist ellipse marked is within the northern portion of flat-lying Elysium Planitia about four degrees north of Mars' equator.

Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech

After a 205-day journey that began on May 5, NASA's InSight mission will touch down on Mars on Nov. 26 a little before 3 p.m. EST (12 p.m. PST). Its solar panels will unfurl within a few hours of touchdown. Mission engineers and scientists will take their time assessing their "workspace" prior to deploying SEIS and HP3 on the surface – about three months after landing – and begin the science in earnest.

InSight was the 12th selection in NASA's series of Discovery-class missions. Created in 1992, the Discovery Program sponsors frequent, cost-capped solar system exploration missions with highly focused scientific goals.

JPL manages InSight for NASA's Science Mission Directorate. InSight is part of NASA's Discovery Program, managed by the agency's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. Lockheed Martin Space in Denver built the InSight spacecraft, including its cruise stage and lander, and supports spacecraft operations for the misión.

A number of European partners, including France's Centre National d'Études Spatiales (CNES) and the German Aerospace Center (DLR), support the InSight mission. CNES provided the SEIS instrument, with significant contributions from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) in Germany, the Swiss Institute of Technology (ETH) in Switzerland, Imperial College and Oxford University in the United Kingdom, and JPL. DLR provided the HP3 instrument.

For more information about InSight, visit:

https://mars.nasa.gov/insight/

https://mars.nasa.gov

DC Agle

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

818-393-9011

agle@jpl.nasa.gov

Dwayne Brown / JoAnna Wendel

NASA Headquarters, Washington

202-358-1726 / 202-358-1003

dwayne.c.brown@nasa.gov / joanna.r.wendel@nasa.gov

2018-258

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

818-393-9011

agle@jpl.nasa.gov

Dwayne Brown / JoAnna Wendel

NASA Headquarters, Washington

202-358-1726 / 202-358-1003

dwayne.c.brown@nasa.gov / joanna.r.wendel@nasa.gov

2018-258

Last Updated: Nov. 21, 2018

Editor: Tony Greicius

NASA

Guillermo Gonzalo Sánchez Achutegui

Inscríbete en el Foro del blog y participa : A Vuelo De Un Quinde - El Foro!

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario