Hola amigos: A VUELO DE UN QUINDE EL BLOG., hemos recopilado información de la Agencia Espacial NASA y de Estación Espacial Europea ESA, sobre la existencia de agua congelada en al superficie y entornos de los cometas, la amplia experiencia de ESA, con su sonda Rosetta que llegó al Cometa 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko en agosto de 2014, se pudo apreciar que los cometas son cuerpos celestes formados por una mezcla de polvo y hielo que mudan de forma periódica cuando pasan por el tramo más próximo al Sol de sus trayectorias elípticas.

Mas información..

Por favor lea amplia literatura abajo adjunta...

Rosetta Desvela el Ciclo del Agua en el Cometa

25.09.15.- La sonda Rosetta de la ESA ha encontrado pruebas que confirman la existencia de un ciclo diario del agua congelada en la superficie y en el entorno del cometa. Los cometas son cuerpos celestes formados por una mezcla de polvo y hielo, que mudan de forma periódica cuando pasan por el tramo más próximo al Sol de sus trayectorias elípticas.

Cuando el Sol calienta el núcleo congelado de un cometa, sus hielos – principalmente de agua, pero también de otros compuestos volátiles como el monóxido o el dióxido de carbono – pasan directamente a estado gaseoso. Este gas se aleja del cometa, arrastrando consigo partículas de polvo. Juntos, el polvo y el gas forman el brillante halo y las características colas de los cometas.

Rosetta llegó al cometa 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko en agosto de 2014, y ha estado estudiándolo de cerca desde aquella. El 13 de agosto de 2015 el cometa pasó por el punto más próximo al Sol de su trayectoria, y ahora se dirige de vuelta al Sistema Solar exterior. Uno de los principales objetivos científicos de la misión Rosetta es comprender los mecanismos que regulan la actividad y las emisiones del cometa, y para ello se está estudiando cómo evoluciona el entorno de 67P desde la llegada de la sonda europea.

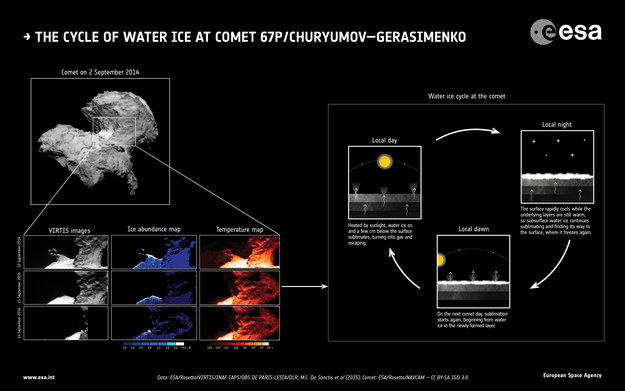

El equipo de científicos encargado del Espectrómetro Térmico en el Visible y en el Infrarrojo (VIRTIS) de Rosetta ha detectado una región en la superficie del cometa en la que el agua congelada aparece y desaparece en sincronía con la rotación de 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. Los resultados de este estudio se publicaron ayer en la revista Nature.

“Hemos descubierto un mecanismo que cubre la superficie del cometa con hielo fresco en cada rotación, lo que mantiene ‘vivo’ al cometa”, explica María Cristina De Sanctis del INAF-IAPS de Roma, Italia, autora principal de este estudio. Su equipo estudió los datos recogidos por Rosetta en septiembre de 2014, centrándose en una región de un kilómetro cuadrado situada en el ‘cuello’ del cometa. Por aquel entonces, el cometa se encontraba a unos 500 millones de kilómetros del Sol y su cuello era una de sus regiones más activas.

|

| El ciclo del agua en el cometa de Rosetta (click para ampliar). Image Credit: ESA |

El cometa tarda un poco más de 12 horas en dar una vuelta completa sobre sí mismo, y mientras gira, sus diferentes regiones experimentan distintas condiciones de iluminación. “Encontramos las huellas del agua congelada en los espectros de esta región, pero sólo cuando se encontraba a la sombra”, aclara María Cristina. “Cuando el Sol la volvía a iluminar, el hielo desaparecía. Esto indica que el hielo de agua está experimentando cambios cíclicos asociados con la rotación del cometa”.

Los datos sugieren que el agua congelada en la superficie y a unos pocos centímetros bajo ella se ‘sublima’ cuando recibe la luz del Sol, transformándose en gas que escapa del cometa. Cuando el cometa gira y esta misma región se queda a la sombra, la superficie se vuelve a enfriar rápidamente. Sin embargo, parece que las capas del subsuelo mantienen parte del calor que recibieron durante las horas de iluminación, y el hielo se sigue sublimando bajo la superficie, abriéndose paso a través del interior poroso del núcleo del cometa.

En cuanto estos vapores ‘subterráneos’ llegan a la gélida superficie, se congelan de nuevo, creando una fina capa de hielo fresco. Finalmente, cuando el Sol vuelve a iluminar esta región al día siguiente, los cristales de hielo recién formados son los primeros en sublimar y escapar del cometa, reiniciando el ciclo.

“Sospechábamos que existía un ciclo de estas características en los cometas, basándonos en los modelos teóricos y en las observaciones de otros cometas, pero ahora, gracias al exhaustivo estudio del cometa 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko que está realizando Rosetta, por fin tenemos pruebas firmes de su existencia”, explica Fabrizio Capaccioni, investigador principal de VIRTIS en el INAF-IAPS de Roma, Italia.

A partir de estos datos, se puede estimar la abundancia relativa de agua en el cometa. A una profundidad de unos pocos centímetros en la región estudiada, el agua congelada constituye un 10-15% de la materia, y parece estar bien mezclada con otras sustancias. Los científicos también han calculado cuánto vapor de agua estaba emitiendo la región que analizaron con VIRTIS, y descubrieron que era un 3% de las emisiones totales del cometa, determinadas por el sensor de microondas MIRO de Rosetta.

“Es posible que muchas regiones de la superficie del cometa estén experimentando el mismo tipo de comportamiento cíclico, realizando una contribución adicional a las emisiones del cometa”, añade Capaccioni. Los científicos ya están analizando los datos recogidos por VIRTIS en los meses posteriores, cuando la actividad del cometa aumentó de forma sustancial mientras pasaba por el tramo más próximo al Sol de su trayectoria.

“Es posible que muchas regiones de la superficie del cometa estén experimentando el mismo tipo de comportamiento cíclico, realizando una contribución adicional a las emisiones del cometa”, añade Capaccioni. Los científicos ya están analizando los datos recogidos por VIRTIS en los meses posteriores, cuando la actividad del cometa aumentó de forma sustancial mientras pasaba por el tramo más próximo al Sol de su trayectoria.

“Estos primeros resultados nos permiten echar un vistazo a lo que está ocurriendo bajo la superficie, en el interior del cometa”, concluye Matt Taylor, científico del proyecto Rosetta para la ESA. “Rosetta es capaz de detectar cambios en el cometa a corto y a largo plazo, por lo que estamos deseando juntar todos estos datos para comprender cómo han evolucionado éste y muchos otros cometas”.

información de NASA en español

Rosetta's target: comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko

There are hundreds of comets flying around the Solar System, each of them a potential target for ESA's comet-chasing Rosetta mission. As the mission took shape, the science team was faced with the difficult task of sifting through these candidates until they identified a handful of suitable objects.

| Rosetta's twelve-year journey in space. Credit: ESA. (Click here for further details and larger versions of this video.) |

Of particular interest were comets that had been observed over at least several orbits of the Sun, and which were known to be fairly active. Ideally, they had to follow orbital paths near the ecliptic plane, so that a rendezvous, prolonged survey and landing would be easier to achieve. Furthermore, the comet's flight into the inner Solar System had to coincide with the mission timeline of Rosetta, so that they both arrived in the right place at the right time for the historic rendezvous.

The favoured target for Rosetta was the periodic comet 46P/Wirtanen, but, after the launch was delayed, another regular visitor to the inner Solar System, 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, was selected as a suitable replacement.

Like all comets, Churyumov-Gerasimenko is named after its discoverers. It was first observed in 1969, when several astronomers from Kiev visited the Alma-Ata Astrophysical Institute in Kazakhstan to conduct a survey of comets.

|

| Astronomer Klim Churyumov, ESA Director General Jean-Jacques Dordain and astronomer Svetlana Gerasimenko, pictured in 2004. Credit: Christian Sotty |

On 20 September, Klim Churyumov was examining a photograph of comet 32P/Comas Solá, taken by Svetlana Gerasimenko, when he noticed another comet-like object. After returning to Kiev, he studied the plate very carefully and eventually realised that they had indeed discovered a new comet.

Comet 67P is one of numerous short period comets which have orbital periods of less than 20 years and a low orbital inclination. Since their orbits are controlled by Jupiter's gravity, they are also called Jupiter Family comets.

These comets are believed to originate from the Kuiper Belt, a large reservoir of small icy bodies located just beyond Neptune. As a result of collisions or gravitational perturbations, some of these icy objects are ejected from the Kuiper Belt and fall towards the Sun.

When they cross the orbit of Jupiter, the comets gravitationally interact with the massive planet. Their orbits gradually change as a result of these interactions until they are eventually thrown out of the Solar System or collide with a planet or the Sun.

Churyumov-Gerasimenko reflects the steplike process of how encounters with Jupiter push a comet further into the inner Solar System. Analysis of its orbital evolution shows that, up to 1840, its perihelion distance – closest approach to the Sun - was 4.0 AU (four Sun-Earth distances or about 600 million km). This was too far from the Sun's heat for the ice-rich nucleus to vaporise and for tails to develop. This meant that the dormant comet was unobservable from Earth.

That year, a fairly close encounter with Jupiter caused the orbit to move inwards to a perihelion distance of 3.0 AU (450 million km). Over the next century, the perihelion gradually decreased further to 2.77 AU. Then, in 1959, another Jupiter encounter reduced the comet's perihelion to just 1.29 AU – which has changed little ever since. It currently completes one orbit of the Sun every 6.45 years.

The comet has now been observed from Earth on seven approaches to the Sun - 1969 (discovery), 1976, 1982, 1989, 1996, 2002 and 2009. Like all comets, it has a fairly small, solid nucleus which is thought to resemble a dirty snowball.

|

| Sequence of Rosetta navigation camera images taken between 1 and 6 August 2014, during the approach to comet 67P. Credit: ESA/Rosetta/NAVCAM |

The density of the nucleus seems to be much lower than that of water, indicating a loosely packed or porous object. Like other comets, its nucleus is generally blacker than coal, indicating a surface layer or crust of carbon-rich organic material.

We still know very little about the surface properties of the nucleus, so the selection of a suitable landing site for the Philae probe will only be possible after the arrival of Rosetta in August 2014, followed by a detailed survey from close quarters.

When Rosetta arrives at the comet it will be at a distance of about three Astronomical Units (450 million km) from the Sun. As it moves towards the Sun, the ice in the nucleus begins to sublimate and the comet begins to eject increasing amounts of dust. Ejection of micron-sized grains starts at about 4.3 AU, but millimetre-sized grains are more likely to appear between 3.4 and 3.2 AU. This leads to the development of a coma (a diffuse cloud of dust and gas surrounding the solid nucleus) and subsequently a tail of dust that trails away from the Sun. Early observations of the comet showed some evidence for variable activity between April and June 2014, with the coma brightening rapidly and then dying down again over a period of about six weeks. Approaching from the sunward side of the comet's orbit, the spacecraft should encounter less dust, with a low probability of being disabled by a large impact.

During the 2002/2003 apparition, the tail was up to 10 arc minutes long as seen from Earth, with a bright central condensation in a faint extended coma. Seven months after perihelion the tail continued to be very well developed, although it subsequently faded rapidly.

As is the case with most comets, activity is not evenly distributed on the surface of the nucleus and the coma of 67P is fed by several dust jets - at least three prominent active areas were identified during the 2009 apparition. In general, a rapid increase in cometary activity could be a problem for Rosetta, so the mission team plans to move the spacecraft further from the nucleus as the level of activity increases beyond an acceptable level.

|

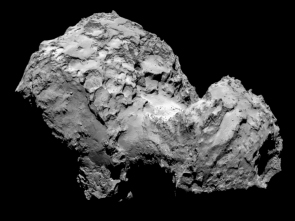

| Comet 67P by Rosetta's OSIRIS narrow-angle camera on 3 August 2014. Credit: ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA |

Even at its peak of activity about one month after perihelion, the comet is not very bright, with a typical visual magnitude of around 12, meaning that it will require a telescope to see it from Earth.

Comet 67P is classed as a dusty comet, with a dust to gas emission ratio of approximately 2:1. The peak dust production rate in 2002/03 was estimated at approximately 60 kg per second, although values as high as 220 kg per second were reported in 1982/83.

Sixty-one images of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko were taken with the Wide Field Planetary Camera 2 on board the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) on 11-12 March 2003. The HST's sharp vision enabled astronomers to isolate the comet's nucleus from the coma. The images showed that the nucleus measures roughly five by three kilometres and has an approximately ellipsoidal (rugby ball) shape.

These results were independently confirmed by some of the largest ground-based telescopes, including the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope, by observing the comet when it was inactive at large distance from the Sun.

Changes in its light curve appear to be closely linked with the effective radius of the nucleus as it rotates, rather than with variations in its surface albedo (brightness). These observations indicate that it spins once in approximately 12 hours.

Its axial inclination, orientation and direction of spin are still uncertain, although recent observations suggest that the axis is tilted about 40 degrees. This means that, as the comet approaches the Sun, its northern hemisphere is illuminated while part of the southern hemisphere is in darkness. During that period, no jets are visible.

The Sun is overhead at the comet's equator about 120 days before perihelion. If the comet behaves as in 2003 and 2009, the main jets should become visible a month before perihelion, i.e. mid-July 2015. This late onset of major activity will be good news for anyone concerned with the safety of Rosetta and its Philae lander.

Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko

| |

| Size of nucleus: Small lobe Large lobe | 2.5 km x 2.5 km x 2.0 km 4.1 km x 3.2 km x 1.3 km |

| Mass | 1013 kg |

| Volume | 25 km3 |

| Density | 0.4 g/cm3 |

| Rotation period | 12.4043 ± 0.0007 * hours |

| Spin axis | Right ascension: 69 degrees Declination: 64 degrees |

| Orbital period | 6.55 years |

| Perihelion distance from Sun | 186 million km (1.243 AU) |

| Aphelion distance from Sun | 849.7 million km (5.68 AU) |

| Orbital eccentricity | 0.640 |

| Orbital inclination | 7.04 degrees |

| Water vapour production rate | 300 ml/s (June 2014) 1-5 l/s (July-August 2014) |

| Surface temperature | 2-5-230 K (July - August 2014) |

| Subsurface temperature | 30-160 K (August 2014) |

| Gases detected | water, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, ammonia, methane, methanol, sodium, magnesium |

| Dust grains | A few tens of microns to a few hundreds of microns |

| Year of discovery | 1969 |

| Discoverers | Klim Churyumov & Svetlana Gerasimenko |

| * Reference: Mottola, S. et al. [2014] | |

Información de ESA

Guillermo Gonzalo Sánchez Achutegui

Inscríbete en el Foro del blog y participa : A Vuelo De Un Quinde - El Foro!

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario