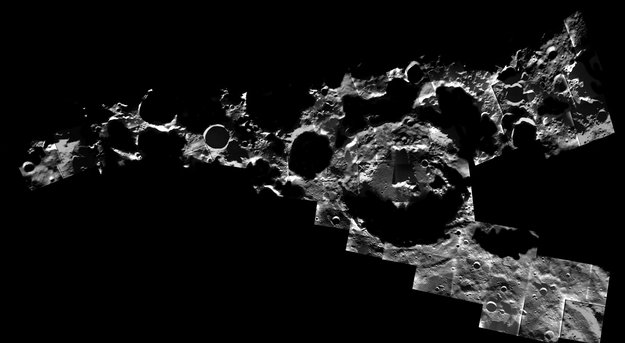

El polo Sur lunar salpicado de cráteres

26 mayo 2014

Las regiones oscuras y sombrías de la Luna fascinan tanto a los astrónomos como a los fans de Pink Floyd. El eje de rotación de nuestro satélite natural se ha inclinado 1.5º, lo que significa que en sus polos hay puntos que nunca ven la luz del sol. El fondo de algunos cráteres, por ejemplo, siempre está en sombra.

Esta imagen mosaico, obtenida con el instrumento Advanced Moon Imaging Experiment de la nave de la ESA SMART-1 , muestra una región salpicada de cráteres en el polo Sur lunar. Obtenida durante el verano del hemisferio sur lunar entre diciembre de 2005 y marzo de 2006, la imagen está compuesta por unas 40 fotos individuales que cubren un área de 500 x 150 km.

Los cráteres en la imagen son (de derecha a izquierda y a partir de la mayor forma circular): Amundsen, Faustini, Shoemaker, Shackleton y de Gerlache.

Amundsen, de 105 Km de diámetro, es el mayor del grupo, seguido de Shoemaker (50 km), Faustini (39 km), de Gerlache (32 km) y Shackleton (19 km). Todos los cráteres tienen características interesantes, y reciben cantidades distintas de luz solar.

El polo Sur lunar está en el borde del cráter Shackleton, el pequeño círculo visible a la izquierda del centro de la imagen. Los investigadores han demostrado que este cráter es más antiguo que la región donde aterrizó el módulo Apolo 15 (3.300 millones de años), pero más reciente que la escogida para el Apolo 14 (3.850 millones de años).

El cráter Shoemaker, visible a la izquierda de la parte central, arriba, es donde se produjo en 1999 el impacto deliberado de la misión Lunar Prospector. El objetivo entonces era determinar la posible presencia de agua , que el calor generado en el choque habría transformado en una columna detectable de vapor de agua. Finalmente no se detectó vapor de agua, pero la posibilidad de que haya agua en la Luna no se ha descartado en absoluto: aún es posible que las regiones que llevan millones de años en permanente sombra alberguen hielo de agua procedente de cometas o asteroides.

El estudio de las oscuras profundidades de estos cráteres podría darnos mucha información no solo sobre la historia de la Luna, sino también sobre la Tierra; nos ayudarían a entender cuánta agua y materia orgánica han pasado de la Luna a la Tierra, y de qué manera.

A peppering of craters at the Moon’s south pole

VERSION ENGLISH

The dark and shadowed regions of the Moon fascinate astronomers and Pink Floyd fans alike. Our Moon’s rotation axis has a tilt of 1.5º, meaning that some parts of its polar regions never see sunlight – the bottoms of certain craters, for example, are always in shadow.

Imaged during summertime in the Moon’s southern hemisphere by the Advanced Moon Imaging Experiment on ESA’s SMART-1 spacecraft, this mosaic shows a crater-riddled region spanning the lunar south pole. It is made up of around 40 individual images taken between December 2005 and March 2006, and covers an area of about 500 x 150 km.

The craters visible here include (from right to left, starting with the largest round shape visible in the frame) the Amundsen, Faustini, Shoemaker, Shackleton and de Gerlache craters. Click here for an annotated map.

Amundsen is the largest of the bunch at 105 km across, followed by Shoemaker (50 km), Faustini (39 km), de Gerlache (32 km) and Shackleton (19 km). This group of craters all look different, see varying levels of sunlight and display a range of interesting properties.

Shackleton crater, the small circle visible to the left of centre, contains the south pole within its rim. By using SMART-1 images to explore the number of small impact craters scattered on the smooth, dark surface surrounding Shackleton, scientists have found this crater to be older than the Apollo 15 landing site (3.3 billion years), but younger than the Apollo 14 site (3.85 billion years).

Shoemaker crater, visible to the upper left of centre, is notable because of the 1999 Lunar Prospector mission, which deliberately crashed into the crater in an attempt to create a detectable plume of water vapour by heating any water ice that may have been present. No vapour was spotted. However, all is not lost; some permanently shadowed regions have been in the dark for millions of years, and it is still possible that they may contain water ice deposited by comets and water-rich asteroids.

Studying the dark depths of these craters could tell us not just about the history of the Moon, but also about Earth, helping us to understand better how, and how much, water and organic material may have been transferred from the Moon to Earth over its history.

RELATED IMAGES:

Follow us

ESA

Guillermo Gonzalo Sánchez Achutegui

ESA Space Science Image of the Week on Flickr

ESA Space Science Image of the Week on Flickr  ESA 3D on Flickr

ESA 3D on Flickr  ESA Sci on Twitter

ESA Sci on Twitter

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario