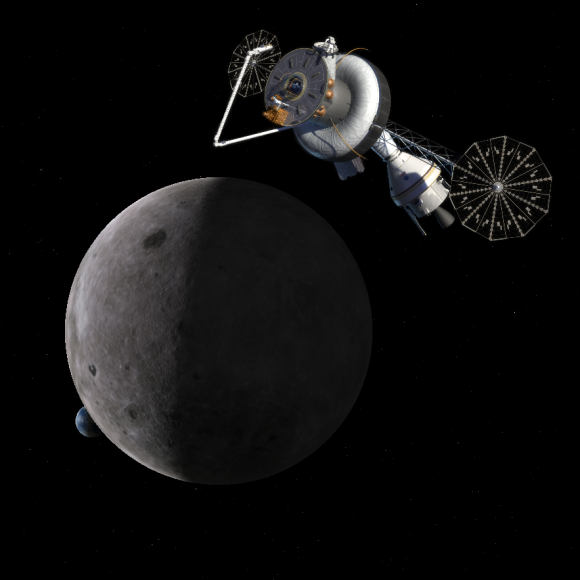

NASA proposal for a future deep space station, 'parked' at lunar

Lagrange point 2 past the far side of the Moon. Residing beyond Earth's

magnetic field, its occupants would need enhanced radiation protection.

Credits: NASA

Humans venturing beyond Earth orbit deeper into space face increased

exposure to cosmic radiation, so ESA has teamed with Germany’s GSI

particle accelerator to test potential shielding for astronauts,

including Moon and Mars soil.

ESA’s two-year project is assessing the most promising materials for shielding future astronauts going to the Moon, the asteroids or Mars.

ESA’s two-year project is assessing the most promising materials for shielding future astronauts going to the Moon, the asteroids or Mars.

“We are working with the only facility in Europe capable of simulating

the high-energy heavy atomic nuclei found in galactic cosmic radiation –

the GSI Helmholtz Centre for Heavy Ion Research in Darmstadt, Germany,”

explained Alessandra Menicucci, overseeing the project.

“We assessed materials including aluminium, water, polyethylene plastic,

multilayer structures and simulated Moon and Mars material – the latter

on the basis these will be accessible to planetary expeditions

Lunar regolith simulant JSC-1A

Credits: NASA

“We have also confirmed a new type of hydrogen storage material holds particular promise.”

Space is awash with charged particles, meaning that astronauts are officially classed as radiation workers.

The International Space Station orbits within Earth’s magnetic field,

safeguarding its occupants from the bulk of space radiation. To venture

further out, dedicated shielding will be required.

Space radiation comes from the Sun – in the form of intense but

short-lived ‘solar particle events’ – as well as galactic cosmic

radiation originating beyond our Solar System: atomic nuclei produced by

dying stars, their passage sped by magnetic fields as they cross the

galaxy.

Download:

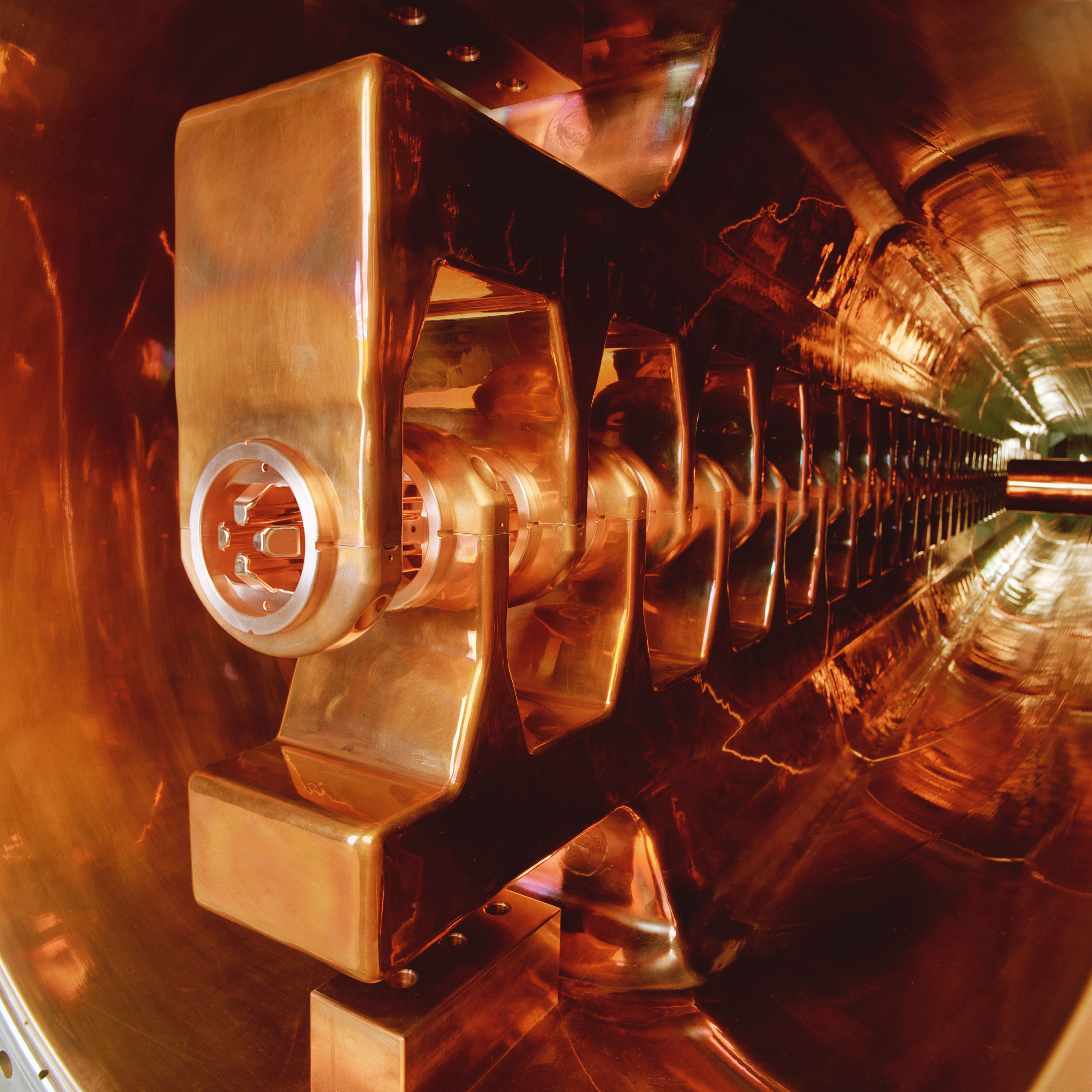

GSI's linear accelerator UNILAC (UNIversal Linear ACcelerator) has a

length of 120 meters. Ions, e.g. charged atoms of all chemical elements

can be accelerated up to 20 percent of the speed of light (60,000 km/s)

with this unit.

Credits: GSI

"Solar particle events are made up of protons that can be shielded quite simply,” added Alessandra.

“The real challenge for deep-space missions is galactic cosmic

radiation, which cannot be shielded completely because of its very high

energy, although the exposure level decreases with increased solar

activity.

Most are small protons or helium nuclei, but about 1% are larger, the

size of an iron atom or more – known as ‘high-ionising high energy

particles’ or HZE for short.

Radiation shielding can be counter-intuitive because denser and thicker does not always mean better.

Discovery's spacewalkers Stephen Bowen and Al Drew working outside the ISS. ESA's Paolo Nespoli took this photo on 28 February 2011.

Credits: ESA/NASA

HZEs striking metal shields can produce showers of secondary particles that might be even more harmful.

And as shield thickness increases, overall the energy loss of ionising radiation rises to a peak then declines rapidly.

“In general, the lighter a material’s atomic nuclei the better the protection,” notes Alessandra.

Water and polyethylene performed better than aluminium for instance, and

new hydrogen-rich materials developed by UK company Cella Energy tested

better still.

Cella Energy originally developed its patent-pending materials for

storing hydrogen fuel but is currently investigating their radiation

resistance.

Read more

ESA.

Guillermo Gonzalo Sánchez Achutegui

ayabaca@gmail.com

ayabaca@hotmail.com

ayabaca@yahoo.com

Inscríbete en el Foro del blog y participa : A Vuelo De Un Quinde - El Foro!

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario