Rosetta captures comet outburst

25 August 2016

In unprecedented observations made earlier this year, Rosetta unexpectedly captured a dramatic comet outburst that may have been triggered by a landslide.

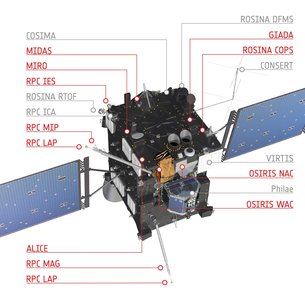

Nine of Rosetta’s instruments, including its cameras, dust collectors, and gas and plasma analysers, were monitoring the comet from about 35 km in a coordinated planned sequence when the outburst happened on 19 February.

“Over the last year, Rosetta has shown that although activity can be prolonged, when it comes to outbursts, the timing is highly unpredictable, so catching an event like this was pure luck,” says Matt Taylor, ESA’s Rosetta project scientist.

“By happy coincidence, we were pointing the majority of instruments at the comet at this time, and having these simultaneous measurements provides us with the most complete set of data on an outburst ever collected.”

The data were sent to Earth only a few days after the outburst, but subsequent analysis has allowed a clear chain of events to be reconstructed, as described in a paper led by Eberhard Grün of the Max-Planck-Institute for Nuclear Physics, Heidelberg, accepted for publication in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

A strong brightening of the comet’s dusty coma was seen by the OSIRIS wide-angle camera at 09:40 GMT, developing in a region of the comet that was initially in shadow.

Over the next two hours, Rosetta recorded outburst signatures that exceeded background levels in some instruments by factors of up to a hundred. For example, between about 10:00–11:00 GMT, ALICE saw the ultraviolet brightness of the sunlight reflected by the nucleus and the emitted dust increase by a factor of six, while ROSINA and RPC detected a significant increase in gas and plasma, respectively, around the spacecraft, by a factor of 1.5–2.5.

In addition, MIRO recorded a 30ºC rise in temperature of the surrounding gas.

Shortly after, Rosetta was blasted by dust: GIADA recorded a maximum hit count at around 11:15 GMT. Almost 200 particles were detected in the following three hours, compared with a typical rate of 3–10 collected on other days in the same month.

At the same time, OSIRIS narrow-angle camera images began registering dust grains emitted during the blast. Between 11:10 GMT and 11:40 GMT, a transition occurred from grains that were distant or slow enough to appear as points in the images, to those either close or fast enough to be captured as trails during the exposures.

In addition, the startrackers, which are used to navigate and help control Rosetta’s attitude, measured an increase in light scattered from dust particles as a result of the outburst.

The startrackers are mounted at 90º to the side of the spacecraft that hosts the majority of science instruments, so they offered a unique insight into the 3D structure and evolution of the outburst.

Astronomers on Earth also noted an increase in coma density in the days after the outburst.

By examining all of the available data, scientists believe they have identified the source of the outburst.

“From Rosetta’s observations, we believe the outburst originated from a steep slope on the comet’s large lobe, in the Atum region,” says Eberhard.

The fact that the outburst started when this area just emerged from shadow suggests that thermal stresses in the surface material may have triggered a landslide that exposed fresh water ice to direct solar illumination. The ice then immediately turned to gas, dragging surrounding dust with it to produce the debris cloud seen by OSIRIS.

“Combining the evidence from the OSIRIS images with the long duration of the GIADA dust impact phase leads us to believe that the dust cone was very broad,” says Eberhard.

“As a result, we think the outburst must have been triggered by a landslide at the surface, rather than a more focused jet bringing fresh material up from within the interior, for example.”

“We’ll continue to analyse the data not only to dig into the details of this particular event, but also to see if it can help us better understand the many other outbursts witnessed over the course of the mission,” adds Matt.

“It’s great to see the instrument teams working together on the important question of how cometary outbursts are triggered.”

Notes for Editors

“The 19 Feb. 2016 outburst of comet 67P/CG: A Rosetta multi-instrument study,” by E. Grün et al is published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. doi: 10.1093/mnras/stw2088

For further information, please contact:

Eberhard Grün

Max-Planck-Institute for Nuclear Physics, Heidelberg, Germany

Email: eberhard.gruen@mpi-hd.mpg.de

Matt Taylor

ESA Rosetta project scientist

Email: matthew.taylor@esa.int

Markus Bauer

ESA Science and Robotic Exploration Communication Officer

Tel: +31 71 565 6799

Mob: +31 61 594 3 954

Email: markus.bauer@esa.int

country > Spain

ESA“The 19 Feb. 2016 outburst of comet 67P/CG: A Rosetta multi-instrument study,” by E. Grün et al is published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. doi: 10.1093/mnras/stw2088

For further information, please contact:

Eberhard Grün

Max-Planck-Institute for Nuclear Physics, Heidelberg, Germany

Email: eberhard.gruen@mpi-hd.mpg.de

Matt Taylor

ESA Rosetta project scientist

Email: matthew.taylor@esa.int

Markus Bauer

ESA Science and Robotic Exploration Communication Officer

Tel: +31 71 565 6799

Mob: +31 61 594 3 954

Email: markus.bauer@esa.int

country > Spain

Rosetta captura una potente emisión

26 agosto 2016 Durante una serie de observaciones sin precedentes a principios de este año, Rosetta capturó inesperadamente una espectacular emisión en 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, quizá provocada por un deslizamiento de tierra.

Cuando se produjo, el 19 de febrero, nueve de los instrumentos de Rosetta, incluidas sus cámaras, colectores de polvo y analizadores de gas y plasma, vigilaban el cometa a unos 35 km de distancia, en una secuencia programada y coordinada.

Como comenta Matt Taylor, científico del proyecto Rosetta de la ESA: “A lo largo del pasado año, Rosetta ha demostrado que, aunque la actividad que provocan puede prolongarse, estas emisiones son altamente impredecibles, por lo que capturar un evento así fue cuestión de suerte”.

“Dio la casualidad de que, en ese momento, la mayoría de los instrumentos apuntaban al cometa y, ahora, todas esas mediciones simultáneas nos ofrecen los datos más completos jamás recogidos sobre una emisión”.

Cuando se produjo, el 19 de febrero, nueve de los instrumentos de Rosetta, incluidas sus cámaras, colectores de polvo y analizadores de gas y plasma, vigilaban el cometa a unos 35 km de distancia, en una secuencia programada y coordinada.

Como comenta Matt Taylor, científico del proyecto Rosetta de la ESA: “A lo largo del pasado año, Rosetta ha demostrado que, aunque la actividad que provocan puede prolongarse, estas emisiones son altamente impredecibles, por lo que capturar un evento así fue cuestión de suerte”.

“Dio la casualidad de que, en ese momento, la mayoría de los instrumentos apuntaban al cometa y, ahora, todas esas mediciones simultáneas nos ofrecen los datos más completos jamás recogidos sobre una emisión”.

Pocos días tras producirse la emisión, los datos recopilados se enviaron a la Tierra, donde su posterior análisis ha permitido reconstruir claramente la cadena de eventos, que se describen en un artículo dirigido por Eberhard Grün, del Instituto Max-Planck de Física Nuclear en Heidelberg, Alemania, y publicado en la revista Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

A las 09:40 GMT, la cámara de gran angular OSIRIS captó en la coma un fuerte brillo que se desarrollaba desde una región del cometa inicialmente en la sombra.

A lo largo de las dos horas siguientes, Rosetta registró datos de la emisión que multiplicaban hasta por cien los niveles base de algunos instrumentos. Por ejemplo, entre las 10:00 y las 11:00 GMT, ALICE detectó el brillo ultravioleta de la luz solar reflejada en el núcleo y un fuerte aumento del polvo emitido, que se sextuplicó. Al mismo tiempo, ROSINA y RPC captaron un aumento significativo de gas y plasma (multiplicándose su densidad por un factor de 1,5–2,5) alrededor del satélite.

Por su parte, MIRO registró un aumento de 30 ºC en la temperatura del gas colindante y, poco después, Rosetta fue azotada por una nube de polvo: el analizador GIADA registró un máximo hacia las 11:15 GMT y, durante las tres horas siguientes, se detectaron casi 200 partículas, cuando en otros días del mismo mes lo normal era detectar de 3 a 10.

Al mismo tiempo, el teleobjetivo de la cámara OSIRIS comenzó a fotografiar los granos de polvo emitidos durante la emisión. Entre las 11:10 GMT y las 11:40 GMT, se produjo una transición en las imágenes, que pasaron de mostrar granos distantes o lo bastante lentos como para aparecer en forma puntos a mostrar estas partículas como estelas debido a su cercanía o velocidad.

Además, los sensores de estrellas utilizados para la navegación y el control de la actitud de Rosetta midieron un aumento en la luz emitida por las partículas de polvo como consecuencia de la emisión.

Gracias a su situación, montados a 90º en el lateral del satélite que aloja la mayoría de los instrumentos científicos, los sensores pudieron ofrecer datos únicos sobre la estructura tridimensional y la evolución de la emisión.

Los astrónomos en la Tierra también detectaron un incremento en la densidad de la coma durante los días siguientes a la emisión.

A lo largo de las dos horas siguientes, Rosetta registró datos de la emisión que multiplicaban hasta por cien los niveles base de algunos instrumentos. Por ejemplo, entre las 10:00 y las 11:00 GMT, ALICE detectó el brillo ultravioleta de la luz solar reflejada en el núcleo y un fuerte aumento del polvo emitido, que se sextuplicó. Al mismo tiempo, ROSINA y RPC captaron un aumento significativo de gas y plasma (multiplicándose su densidad por un factor de 1,5–2,5) alrededor del satélite.

Por su parte, MIRO registró un aumento de 30 ºC en la temperatura del gas colindante y, poco después, Rosetta fue azotada por una nube de polvo: el analizador GIADA registró un máximo hacia las 11:15 GMT y, durante las tres horas siguientes, se detectaron casi 200 partículas, cuando en otros días del mismo mes lo normal era detectar de 3 a 10.

Al mismo tiempo, el teleobjetivo de la cámara OSIRIS comenzó a fotografiar los granos de polvo emitidos durante la emisión. Entre las 11:10 GMT y las 11:40 GMT, se produjo una transición en las imágenes, que pasaron de mostrar granos distantes o lo bastante lentos como para aparecer en forma puntos a mostrar estas partículas como estelas debido a su cercanía o velocidad.

Además, los sensores de estrellas utilizados para la navegación y el control de la actitud de Rosetta midieron un aumento en la luz emitida por las partículas de polvo como consecuencia de la emisión.

Gracias a su situación, montados a 90º en el lateral del satélite que aloja la mayoría de los instrumentos científicos, los sensores pudieron ofrecer datos únicos sobre la estructura tridimensional y la evolución de la emisión.

Los astrónomos en la Tierra también detectaron un incremento en la densidad de la coma durante los días siguientes a la emisión.

Una vez examinados los datos disponibles, los científicos creen haber identificado la fuente de la emisión.

“A partir de las observaciones de Rosetta, creemos que se originó en una pendiente pronunciada en el lóbulo mayor del cometa, en la región de Atum”, explica Eberhard.

El hecho de que la emisión comenzara cuando esta área acababa de salir de la sombra sugiere que la tensión térmica en el material superficial podría haber provocado un deslizamiento de tierra que dejó hielo de agua expuesto a la radiación solar. El hielo se habría evaporado rápidamente, arrastrando polvo consigo hasta producir la nube de residuos detectada por OSIRIS.

“La combinación de las imágenes recogidas por las cámaras de OSIRIS con los datos recopilados por GIADA durante la fase de impacto del polvo nos lleva a pensar que el diámetro del cono de polvo fue de gran tamaño —admite Eberhard—. Por eso creemos que la emisión pudo deberse a un deslizamiento de tierra en la superficie, y no a una ráfaga concreta que expulsara materia desde el interior, por ejemplo”.

Matt añade: “Seguiremos analizando los datos para profundizar en los datos de este evento en concreto, y también para ver si nos ayuda a comprender la multitud de emisiones que hemos detectado a lo largo de nuestra misión”.

“Es fantástico ver cómo los distintos equipos responsables de los instrumentos colaboran para estudiar cómo se originan estas emisiones en los cometas”.

“A partir de las observaciones de Rosetta, creemos que se originó en una pendiente pronunciada en el lóbulo mayor del cometa, en la región de Atum”, explica Eberhard.

El hecho de que la emisión comenzara cuando esta área acababa de salir de la sombra sugiere que la tensión térmica en el material superficial podría haber provocado un deslizamiento de tierra que dejó hielo de agua expuesto a la radiación solar. El hielo se habría evaporado rápidamente, arrastrando polvo consigo hasta producir la nube de residuos detectada por OSIRIS.

“La combinación de las imágenes recogidas por las cámaras de OSIRIS con los datos recopilados por GIADA durante la fase de impacto del polvo nos lleva a pensar que el diámetro del cono de polvo fue de gran tamaño —admite Eberhard—. Por eso creemos que la emisión pudo deberse a un deslizamiento de tierra en la superficie, y no a una ráfaga concreta que expulsara materia desde el interior, por ejemplo”.

Matt añade: “Seguiremos analizando los datos para profundizar en los datos de este evento en concreto, y también para ver si nos ayuda a comprender la multitud de emisiones que hemos detectado a lo largo de nuestra misión”.

“Es fantástico ver cómo los distintos equipos responsables de los instrumentos colaboran para estudiar cómo se originan estas emisiones en los cometas”.

Nota para los editores

El artículo “The 19 Feb. 2016 outburst of comet 67P/CG: A Rosetta multi-instrument study,” de E. Grün et al., está publicado en la revista Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. doi: 10.1093/mnras/stw2088

Para más información:

Eberhard Grün

Max-Planck-Institute for Nuclear Physics, Heidelberg, Germany

Correo electrónico: eberhard.gruen@mpi-hd.mpg.de

Matt Taylor

ESA Rosetta project scientist

Correo electrónico: matthew.taylor@esa.int

Markus Bauer

ESA Science and Robotic Exploration Communication Officer

Teléfono: +31 71 565 6799

Móvil: +31 61 594 3 954

Correo electrónico: markus.bauer@esa.int

El artículo “The 19 Feb. 2016 outburst of comet 67P/CG: A Rosetta multi-instrument study,” de E. Grün et al., está publicado en la revista Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. doi: 10.1093/mnras/stw2088

Para más información:

Eberhard Grün

Max-Planck-Institute for Nuclear Physics, Heidelberg, Germany

Correo electrónico: eberhard.gruen@mpi-hd.mpg.de

Matt Taylor

ESA Rosetta project scientist

Correo electrónico: matthew.taylor@esa.int

Markus Bauer

ESA Science and Robotic Exploration Communication Officer

Teléfono: +31 71 565 6799

Móvil: +31 61 594 3 954

Correo electrónico: markus.bauer@esa.int

Guillermo Gonzalo Sánchez Achutegui

ayabaca@gmail.com

ayabaca@hotmail.com

ayabaca@yahoo.com

Inscríbete en el Foro del blog y participa : A Vuelo De Un Quinde - El Foro!

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario