Hola amigos: A VUELO DE UN QUINDE EL BLOG., lo que los científicos habían previsto sucedió, este miércoles 12 de julio, asombró la información de que se haya desprendido de la Península Antártica un gigantesco iceberg llamado Larsen C, de aproximadamente 6,000 kilómetros cuadrados, y un peso de 1,000 millones de toneladas; equivalente a la extensión un pequeño país europeo como Luxemburgo, que flota a la deriva con dirección al Atlántico Sur. Las Agencias Espaciales como NASA, ESA y otros organismos con sus satélites están haciendo un seguimiento de este gigantesca masa de hielo, se ha calculado que no influirá en el aumento del nivel de las aguas, pero aun así el medio ambiente sufrirá un cambio, con el derretimiento de la masa que será gradual, tomando la información de BBC Mundo Noticias : ".... Según investigadores británicos, estos gigantes de hielo tienen un impacto dramático y pueden alterar incluso los ciclos alimentarios de los animales que habitan la isla.

A esta isla, por ejemplo, llegó el iceberg A-38 en 2004.

"El agua dulce tiene un efecto mensurable en la estructura de la columna de agua", le explicó a la BBC Mark Brandon, oceanógrafo de la Universidad Abierta, en Reino Unido....."

A continuación la información completa de este suceso del medio ambiente....

https://nasasearch.nasa.gov/search?query=Larsen+C&affiliate=nasa&utf8=%E2%9C%93

https://www.nasa.gov/feature/goddard/2017/massive-iceberg-breaks-off-from-antárctica

http://www.esa.int/Our_Activities/Observing_the_Earth/Copernicus/Sentinel-1/Sentinel_satellite_captures_birth_of_behemoth_iceberg

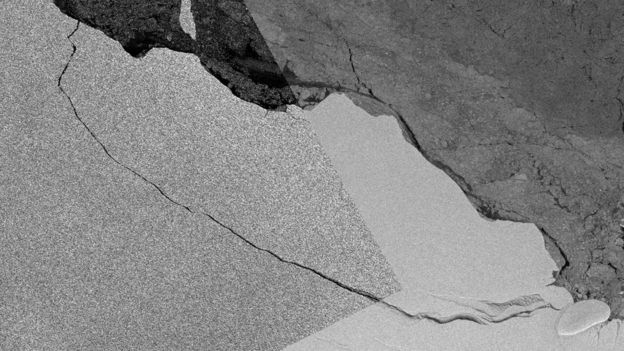

Derechos de autor de la imagen ESA

Derechos de autor de la imagen ESA

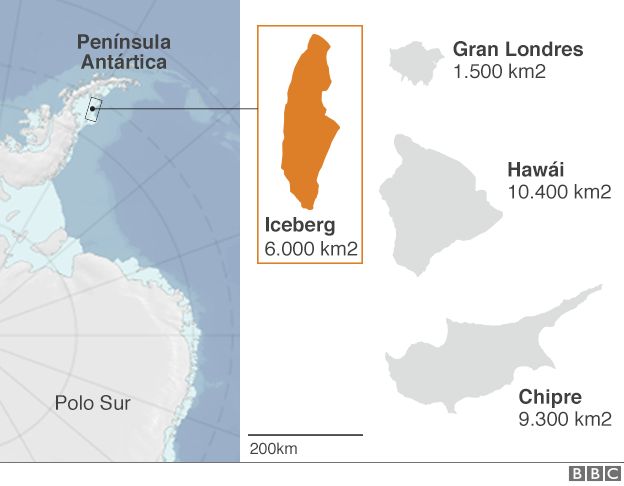

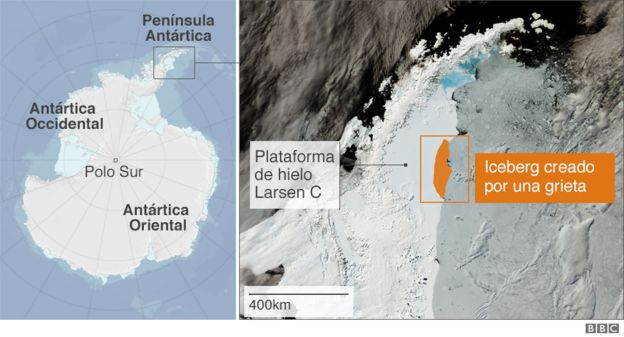

Lo venían anunciado desde hace meses: un gigantesco iceberg de cerca de 6.000 km2 está a punto de desprenderse de la Antártica.

La grieta que mantiene unido a este inmenso bloque de hielo 4 veces más grande que Ciudad de México, 10 que Madrid y equiparable a la mitad de Puerto Rico se está expandiendo, insistían los científicos.

Y finalmente, este miércoles, esta enorme masa de hielo de 1 billón de toneladas se separó definitivamente de la Plataforma de Hielo Larsen C.

Ahora que ya cortó sus lazos con la plataforma, ¿qué pasará con el témpano que probablemente recibirá el nombre de A-68?

Derechos de autor de la imagen Copernicus Sentinel (2017) ESA/Andrew Flemming

Derechos de autor de la imagen Copernicus Sentinel (2017) ESA/Andrew Flemming

¿Quedará a la deriva en el océano, poniendo en peligro a los barcos que navegan por la región?

Rumbo norte

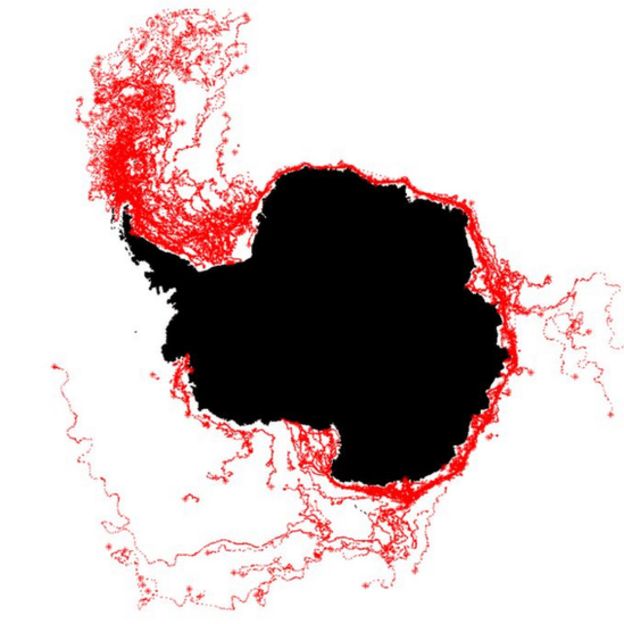

"El movimiento de los icebergs está controlado mayormente por los vientos de la atmósfera y las corrientes oceánicas que empujan al bloque de hielo que está por debajo de la superficie del agua", le explica a BBC Mundo Anna Hogg, experta en observaciones satelitales de la Universidad de Leeds, en Reino Unido.

Derechos de autor de la imagen Esa

Derechos de autor de la imagen Esa  Derechos de autor de la imagen Atlas del Submarine Glacial Landforms

Derechos de autor de la imagen Atlas del Submarine Glacial Landforms

Pero también, está determinado por la simetría de lecho marino.

"Los rasgos topográficos importantes, como por ejemplo las pequeñas montañas en el fondo del mar, pueden ser lo suficientemente altas como para hacer que el témpano permanezca en el mismo sitio por un tiempo", dice Hogg.

Si nada lo detiene, o si eventualmente se mueve de su posición original, comenzará a viajar alrededor del continente antártico, impulsado por la corriente costera que gira en sentido contrario a las agujas del reloj y está presente durante todo el año.

Una vez que llegue a la punta de la Península Antártica, "continuará viajando hacia el norte, en dirección al Pasaje de Drake, donde se irá disipando", explica la experta.

Derechos de autor de la imagen AFP

Derechos de autor de la imagen AFP

Este proceso demora meses, años.

"Semejante volumen de hielo, tomará un buen tiempo en derretirse, sin importar si está en aguas frías o más cálidas", señala Hogg.

Peligro

Los científicos no saben con exactitud hasta dónde llegará, pero normalmente no suele llegar hasta una zona habitada.

Y, a medida que se desplaza hacia el norte, se irá rompiendo en fragmentos más pequeños que pueden continuar su viaje en diferentes direcciones, según las fuerzas que actúen sobre ellos.

Derechos de autor de la imagen SPL

Derechos de autor de la imagen SPL

Cuando abandone las inmediaciones del continente antártico, es crucial seguirle la pista, ya que es allí donde puede convertirse en un peligro para los navegantes.

No en este momento -en medio del invierno en el sur-, pero sí durante el verano antártico: si bien la península está fuera de las rutas comerciales más importantes, es el principal destino turístico de los cruceros provenientes de América del Sur.

Mientras se mantiene como una sola pieza, o varias pero grandes, es menos peligroso, ya que puede verse a la distancia. Cuando se desmembra la situación empeora, porque desde la superficie es difícil estimar cuánto hielo hay sumergido bajo el agua.

Georgia del Sur

Uno de los lugares donde también suelen acabar los glaciares grandes es en la plataforma de hielo superficial que rodea la isla de Georgia del Sur, unos 1.390 km al este-sureste de las islas Malvinas/Falklands.

Al desarmarse allí, los icebergs vuelcan miles de millones de toneladas de agua dulce en el ambiente marino local.

Según investigadores británicos, estos gigantes de hielo tienen un impacto dramático y pueden alterar incluso los ciclos alimentarios de los animales que habitan la isla.

A esta isla, por ejemplo, llegó el iceberg A-38 en 2004.

"El agua dulce tiene un efecto mensurable en la estructura de la columna de agua", le explicó a la BBC Mark Brandon, oceanógrafo de la Universidad Abierta, en Reino Unido.

Derechos de autor de la imagen AQUA / MODIS / NASA

Derechos de autor de la imagen AQUA / MODIS / NASA

"Cambia las corrientes en la plataforma porque cambia la densidad del agua de mar. Y también baja la temperatura del agua".

El polvo y los fragmentos de roca que el iceberg trajo de Antártica actúan a modo de nutrientes cuando se derriten en el océano e incrementan la productividad de las algas y las diatomeas en la base de la cadena alimentaria.

Pero en Georgia del Sur, estos glaciares pueden tener un impacto negativo al actuar como barrera contra el influjo de kril, una fuente de alimentos vital para muchos animales de la isla, incluidos pingüinos, focas y aves.

Temas relacionados

Contenido relacionado

BBC Mundo NoticiasInformación de NASA .-

Massive Iceberg Breaks Off from Antarctica

Thermal wavelength image of a large iceberg, which has calved off the Larsen C ice shelf. Darker colors are colder, and brighter colors are warmer, so the rift between the iceberg and the ice shelf appears as a thin line of slightly warmer area. Image from July 12, 2017, from the MODIS instrument on NASA's Aqua satellite.

Credits: NASA Worldview

An iceberg about the size of the state of Delaware split off from Antarctica’s Larsen C ice shelf sometime between July 10 and July 12. The calving of the massive new iceberg was captured by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer on NASA’s Aqua satellite, and confirmed by the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite instrument on the joint NASA/NOAA Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership (Suomi-NPP) satellite. The final breakage was first reported by Project Midas, an Antarctic research project based in the United Kingdom.

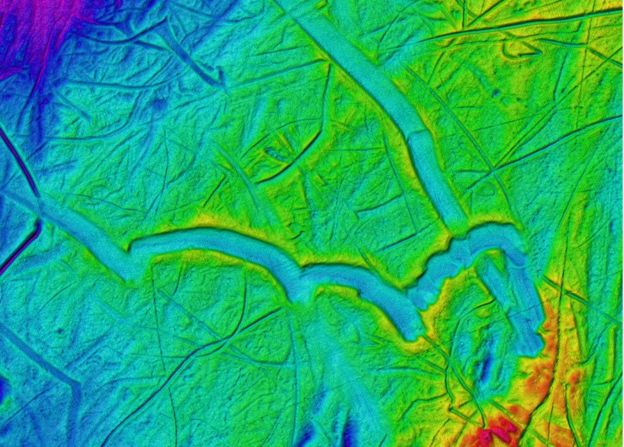

Animation of the growth of the crack in the Larsen C ice shelf, from 2006 to 2017, as recorded by NASA/USGS Landsat satellites.

Credits: NASA/USGS Landsat

Larsen C, a floating platform of glacial ice on the east side of the Antarctic Peninsula, is the fourth largest ice shelf ringing Earth’s southernmost continent. In 2014, a crack that had been slowly growing into the ice shelf for decades suddenly started to spread northwards, creating the nascent iceberg. Now that the close to 2,240 square-mile (5,800 square kilometers) chunk of ice has broken away, the Larsen C shelf area has shrunk by approximately 10 percent.

Throughout the sunlit months of late 2016 and early 2017, scientists watched closely as a crack grew across the Larsen C ice shelf on the Antarctic Peninsula. On June 17, 2017, the Thermal Infrared Sensor (TIRS) on Landsat 8 captured a false-color image of the crack and the surrounding ice shelf. It shows the relative warmth or coolness of the landscape. Orange depicts where the surface is the warmest, most notably the areas of open ocean and of water topped by thin sea ice. Light blues and whites are the coldest areas, spanning most of the ice shelf and some areas of sea ice. Dark blue and purple areas are in the mid-range.

Credits: NASA's Earth Observatory

The blue hue of the crack indicates that relatively warm ocean water is not far below the ice surface. No part of the crack appears as warm as ocean areas, likely because there is a soup of floating, broken ice pieces from the rift’s walls and bits of sea ice sitting atop the water-filled crack. (This mixture can act as a weak glue, but it also prevents the rift from healing.)

Credits: NASA's Earth Observatory

“The interesting thing is what happens next, how the remaining ice shelf responds,” said Kelly Brunt, a glaciologist with NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, and the University of Maryland in College Park. “Will the ice shelf weaken? Or possibly collapse, like its neighbors Larsen A and B? Will the glaciers behind the ice shelf accelerate and have a direct contribution to sea level rise? Or is this just a normal calving event?”

Ice shelves fringe 75 percent of the Antarctic ice sheet. One way to assess the health of ice sheets is to look at their balance: when an ice sheet is in balance, the ice gained through snowfall equals the ice lost through melting and iceberg calving. Even relatively large calving events, where tabular ice chunks the size of Manhattan or bigger calve from the seaward front of the shelf, can be considered normal if the ice sheet is in overall balance. But sometimes ice sheets destabilize, either through the loss of a particularly big iceberg or through disintegration of an ice shelf, such as that of the Larsen A Ice Shelf in 1995 and the Larsen B Ice Shelf in 2002. When floating ice shelves disintegrate, they reduce the resistance to glacial flow and thus allow the grounded glaciers they were buttressing to significantly dump more ice into the ocean, raising sea levels.

Scientists have monitored the progression of the rift throughout the last year was using data from the European Space Agency Sentinel-1 satellites and thermal imagery from NASA’s Landsat 8 spacecraft. Over the next months and years, researchers will monitor the response of Larsen C, and the glaciers that flow into it, through the use of satellite imagery, airborne surveys, automated geophysical instruments and associated field work.

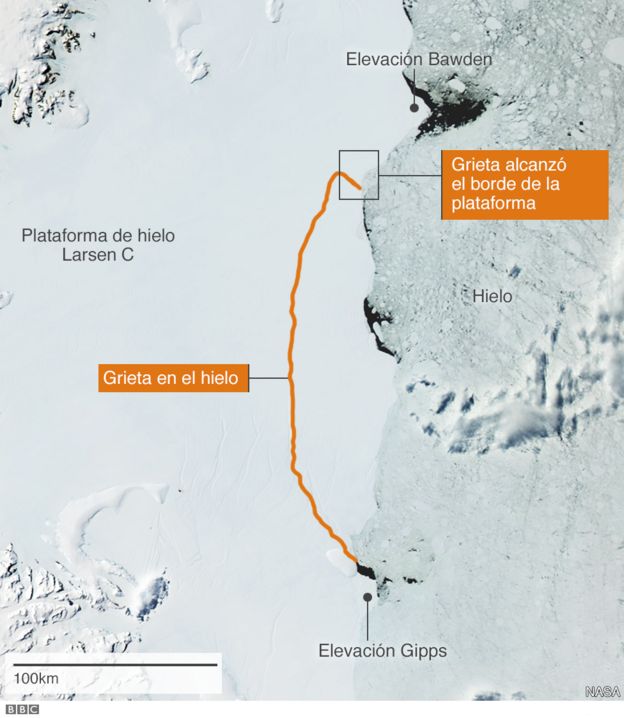

In the case of this rift, scientists were worried about the possible loss of a pinning point that helped keep Larsen C stable. In a shallow part of the sea floor underneath the ice shelf, a bedrock protrusion, named the Bawden Ice Rise, has served as an anchor point for the floating shelf for many decades. Ultimately, the rift stopped short of separating from the protrusion.

“The remaining 90 percent of the ice shelf continues to be held in place by two pinning points: the Bawden Ice Rise to the north of the rift and the Gipps Ice Rise to the south,” said Chris Shuman, a glaciologist with Goddard and the University of Maryland at Baltimore County. “So I just don’ see any near-term signs that this calving event is going to lead to the collapse of the Larsen C ice shelf. But we will be watching closely for signs of further changes across the area.”

The first available images of Larsen C are airborne photographs from the 1960s and an image from a US satellite captured in 1963. The rift that has produced the new iceberg was already identifiable in those pictures, along with a dozen other fractures. The crack remained dormant for decades, stuck in a section of the ice shelf called a suture zone, an area where glaciers flowing into the ice shelf come together. Suture zones are complex and more heterogeneous than the rest of the ice shelf, containing ice with different properties and mechanical strengths, and therefore play an important role in controlling the rate at which rifts grow. In 2014, however, this particular crack started to rapidly grow and traverse the suture zones, leaving scientists perplexed.

“We don’t currently know what changed in 2014 that allowed this rift to push through the suture zone and propagate into the main body of the ice shelf,” said Dan McGrath, a glaciologist at Colorado State University who has been studying the Larsen C ice shelf since 2008.

McGrath said the growth of the crack, given our current understanding, is not directly linked to climate change.

“The Antarctic Peninsula has been one of the fastest warming places on the planet throughout the latter half of the 20th century. This warming has driven really profound environmental changes, including the collapse of Larsen A and B,” McGrath said. “But with the rift on Larsen C, we haven’t made a direct connection with the warming climate. Still, there are definitely mechanisms by which this rift could be linked to climate change, most notably through warmer ocean waters eating away at the base of the shelf.”

While the crack was growing, scientists had a hard time predicting when the nascent iceberg would break away. It’s difficult because there are not enough measurements available on either the forces acting on the rift or the composition of the ice shelf. Further, other poorly observed external factors, such as temperatures, winds, waves and ocean currents, might play an important role in rift growth. Still, this event has provided an important opportunity for researchers to study how ice shelves fracture, with important implications for other ice shelves.

The U.S. National Ice Center will monitor the trajectory of the new iceberg, which is likely to be named A-68. The currents around Antarctica generally dictate the path that the icebergs follow. In this case, the new berg is likely to follow a similar path to the icebergs produced by the collapse of Larsen B: north along the coast of the Peninsula, then northeast into the South Atlantic.

“It’s very unlikely it will cause any trouble for navigation,” Brunt said.

By Maria-Jose Viñas

NASA’s Earth Science Team

Additional media contact: Rani Gran, NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

Last Updated: July 12, 2017

Editor: Rob Garner

NASA

INFORMACIÓN DE LA AGENCIA ESPACIAL EUROPEA - ESA .-

Sentinel satellite captures birth of behemoth iceberg

12 July 2017

Over the last few months, a chunk of Antarctica’s Larsen C ice shelf has been hanging on precariously as a deep crack cut across the ice. Witnessed by the Copernicus Sentinel-1 mission, a lump of ice more than twice the size of Luxembourg has now broken off, spawning one of the largest icebergs on record and changing the outline of the Antarctic Peninsula forever.

The fissure first appeared several years ago, but seemed relatively stable until January 2016, when it began to lengthen.

In January 2017 alone it travelled 20 km, reaching a total length of about 175 km.

After a few weeks of calm, the rift propagated a further 16 km at the end of May, and then extended further at the end of June.

More importantly, as the crack grew, it branched off towards the edge of the shelf, whereas before it had been running parallel to the Weddell Sea.

With just a few km between the end of the fissure and the ocean by early July, the fate of the shelf was sealed.

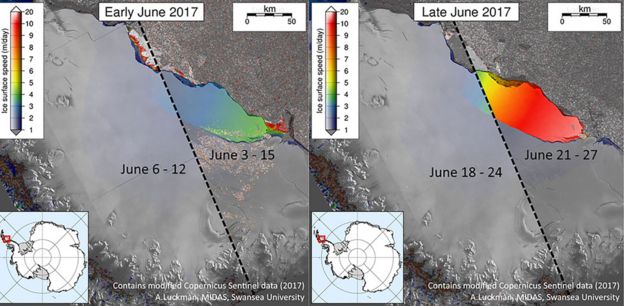

Scientists from Project MIDAS, an Antarctic research consortium led by Swansea University in the UK, used radar images from the Copernicus Sentinel-1 mission to keep a close eye on the rapidly changing situation.

Since Antarctica is heading into the dark winter months, radar images are indispensable because, apart from the region being remote, radar continues to deliver images regardless of the dark and bad weather

Adrian Luckman, leading MIDAS, said, “The recent development in satellite systems like Sentinel-1 has vastly improved our ability to monitor events such as this.”

Noel Gourmelen from the University of Edinburgh added. “We have been using information from ESA’s CryoSat mission, which carries a radar altimeter to measure the surface height and thickness of the ice, to reveal that the crack was several tens of metres deep.”

As predicted, a section of Larsen C – about 6000 sq km – finally broke away as part of the natural cycle of iceberg calving. The behemoth iceberg weighs more than a million million tonnes and contains about the same amount of water as Lake Ontario in North America.

“We have been expecting this for months, but the rapidity of the final rift advance was still a bit of a surprise. We will continue to monitor both the impact of this calving event on the Larsen C ice shelf, and the fate of this huge iceberg,” added Prof. Luckman.

The iceberg’s progress is difficult to predict. It may remain in the area for decades, but if it breaks up, parts may drift north into warmer waters. Since the ice shelf is already floating, this giant iceberg does not influence sea level.

With the calving of the iceberg, about 10% of the area of the ice shelf has been removed.

The loss of such a large piece is of interest because ice shelves along the peninsula play an important role in ‘buttressing’ glaciers that feed ice seaward, effectively slowing their flow.

Previous events further north on the Larsen A and B shelves, captured by ESA’s ERS and Envisat satellites, indicate that when a large portion of an ice shelf is lost, the flow of glaciers behind can accelerate, contributing to sea-level rise.

Thanks to Europe’s Copernicus environmental monitoring programme, we have the Sentinel satellites to deliver essential information about what’s happening to our planet. This is especially important for monitoring remote inaccessible regions like the poles.

ESA’s Mark Drinkwater said, “Having the Copernicus Sentinels in combination with research missions like CryoSat is essential for monitoring ice volume changes in response to climate warming.

“In particular, the combination of year-round data from these microwave-based satellite tools provides critical information with which to understand ice-shelf fracture mechanics and changes in dynamic integrity of Antarctic ice shelves.”

Related articles

Giant iceberg in the making

05 July 2017

05 July 2017

Satellites track Antarctic ice loss over decades

02 May 2017

02 May 2017

Sentinels warn of dangerous ice crack

16 February 2017

16 February 2017

ESA

Guillermo Gonzalo Sánchez Achutegui

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario